This analysis appears in the Special Issue on Nonviolent Approaches to Security.

This analysis summarizes and reflects on the following research: Corburn, J., Boggan, D., & Muttaqi, K. (2021). Urban safety, community healing & gun violence reduction: The Advance Peace model. Urban Transform 3(5). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-021-00021-5

Talking points

In the context of the United States:

- Urban gun violence is most often the result of unaddressed trauma, which can be exacerbated by increased interactions with the criminal legal system.

- A public health-informed approach acknowledging racial trauma and emphasizing individual healing is a promising way to address urban gun violence.

- Deploying formerly incarcerated community members as street outreach mentors to interrupt violence and target influential individuals most involved in gun violence is key to violence reduction.

- Cities should institutionalize peacemaking and gun violence prevention efforts throughout city government instead of having such efforts siloed within law enforcement.

Key Insight for Informing Practice

- Just as we advocate for ceasefires and diplomacy in global conflicts, so too should our city governments, and specifically offices of violence prevention, apply peacebuilding strategies in our own communities to keep civilians safe.

Summary

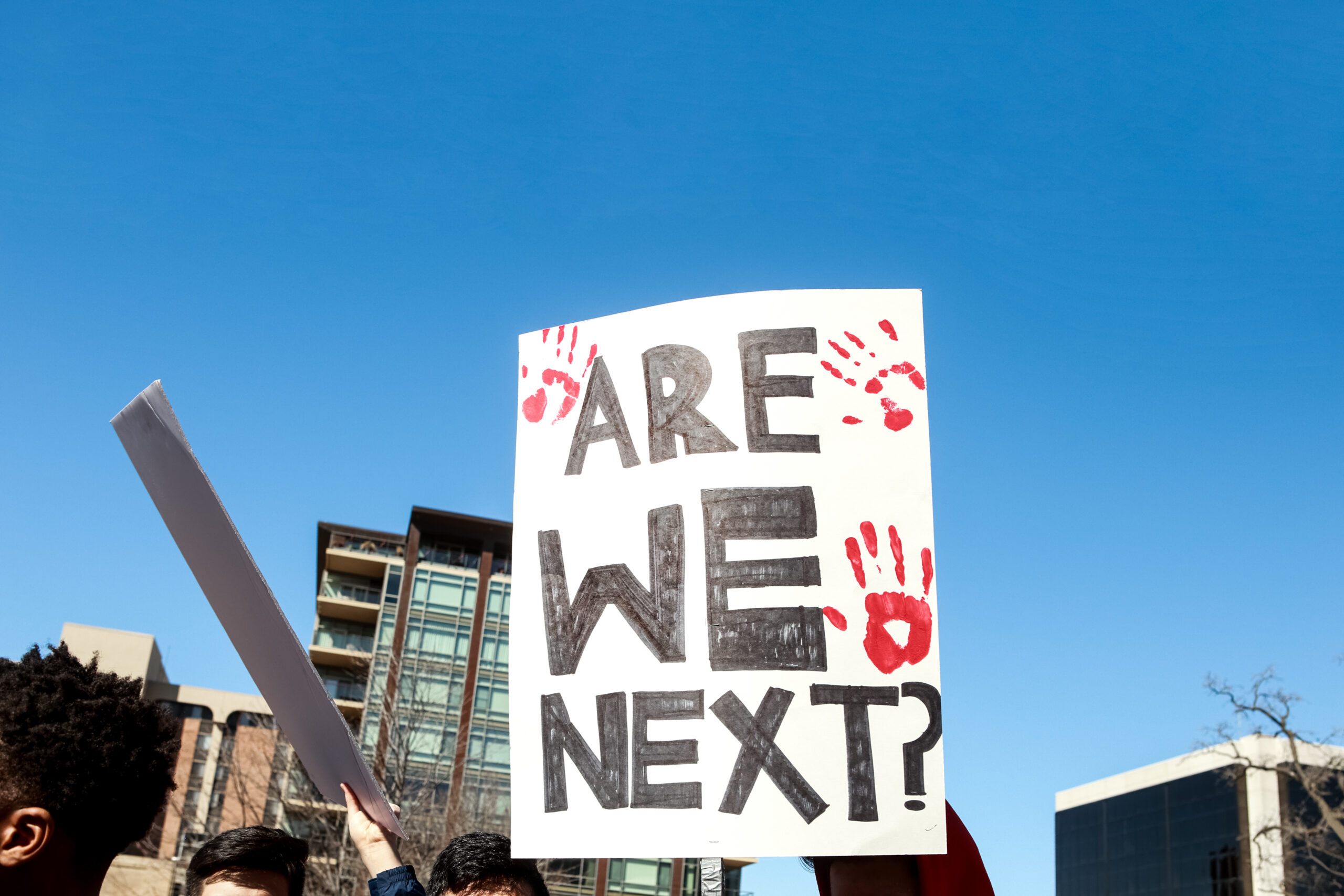

A common response to the epidemic of gun violence in U.S. cities is more law enforcement. However, urban gun violence is most often the result of unaddressed trauma, which can be exacerbated by increased interactions with the criminal legal system. Advance Peace’s Peacemaker Fellowship (PF) offers an innovative approach designed to address the structural violence that contributes to urban gun violence. Drawing from public health interventions, the PF seeks to stop the transmission of violence through a trauma-informed, healing-centered approach. Unlike focused deterrence programs, the PF does not work with police. Intrigued by this innovative approach, Jason Corburn, Devone Boggan, and Khaalid Muttaqi explore the PF in three California cities—Stockton, Sacramento, and Richmond. In their examination, the authors draw out why the PF has proven effective at curbing gun violence.

Pulling from previous research, the authors explain how racism, structural violence, and trauma can contribute to urban gun violence. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Adverse Community Environments compound to create “toxic stressors” that impact an individual’s development and decision-making. ACEs can include physical and sexual abuse, witnessing and being the victim of violence, poverty, homelessness, and interpersonal or institutional racism. Typically occupied by segregated Black, Indigenous, and immigrant communities, Adverse Community Environments are characterized by concentrations of toxic pollution, dilapidated housing, limited green space, low-quality schools, economic divestment, and community violence. Toxic stressors can impact brain development and function, specifically related to decision-making and impulse control. These compounding traumas can lead one to interpret normal and benign circumstances as dangerous. The PF acknowledges these traumas and prioritizes healing. It follows that the PF does not coordinate with law enforcement or utilize dehumanizing policing strategies.

Advance Peace operationalized a framework to address these traumas in their PF. Neighbor Change Agents (NCAs), or formerly incarcerated individuals charged with gun crimes who have successfully reintegrated into society, recruit individuals involved with gun violence to participate in the PF. For 12 months, these recruited individuals, or fellows, are mentored by NCAs. As individuals with life experience that positions them as “credible messengers,” NCAs serve dual roles as violence interrupters and mentors. Fellows and NCAs co-create an individualized healing plan, or LifeMAP, to follow for the duration of the fellowship. Fellows have often never had an adult invest meaningfully in their success, thus the LifeMAP represents a social contract ensuring a responsible, caring adult is doing just that. Progress in their LifeMAP guarantees fellows up to a $1000/month milestone allowance. Additionally, NCAs facilitate transformational travel experiences to visit colleges or conduct community service projects in which fellows must amicably co-exist with rivals from the street who are also in the fellowship. NCAs also refer and accompany their fellows to substance abuse, cognitive behavior therapy, or anger management support services. The fellowship also includes group learning and healing sessions that address institutional and systemic racism, while also celebrating the culture and history of minority groups.

The PF promotes transformation at the individual and community level. In addition to mentoring, NCAs regularly resolve street conflicts and interrupt imminent gun violence incidents. A resolved conflict refers to a general dispute or fight where no guns are present, while imminent gun violence interruption refers to a situation where guns are present or drawn and shooting is imminent. As conflicts are reduced in the community, gun violence is de-normalized. This coupled with the anti-gun messages, nonviolent communication styles, and healthy conflict resolution strategies espoused and modeled by NCAs all contribute to community-level transformation.

The authors compiled the 2019 data from the PF in Richmond, Sacramento, and Stockton. NCAs interrupted 88 imminent gun violence incidents across all cities. Beyond the obvious benefits of preventing the suffering associated with possible injury or death, this prevention of gun violence also has financial implications. In Richmond, NCAs prevented 31 imminent gun violence incidents. Calculating the estimated cost of each firearm injury or homicide in 2019, the program saved the city the equivalent of up to 10% of its budget that year. Of the 197 fellows from the three cities, almost none were injured or were considered a suspect in a gun violence incident after 12 months in the PF program. Considering the fellows’ previous involvement with gun violence, the outcome of this program in their lives is laudable.

The authors make several policy recommendations based on the success of the PF. Cities should adopt a public health-informed approach to gun violence prevention that acknowledges racial trauma and emphasizes individual healing. Moreover, deploying formerly incarcerated community members as street outreach mentors to interrupt violence and target influential individuals most involved in gun violence is key. Finally, cities should institutionalize peacemaking and gun violence prevention efforts throughout city government instead of having such efforts siloed within law enforcement.

Informing Practice

Just as there is a continuum between U.S. defense spending and militarized policing in U.S. towns and cities, so too is there a continuum between the persistent notion that violence can keep us safe in both international and domestic spaces. Yet, Advance Peace’s approach challenges the norm that violence and aggression are best met with increased violence and aggression. Moving away from the principle that increased violence is the most effective solution to stop violence, this intervention focuses on love and healing to address urban gun violence. The success of this approach speaks for itself. Additional evaluations of the PF in Sacramento demonstrate that the intervention reduced gun homicides and assaults city-wide by 10%. As communities across the country face increasing violence, more attention should be focused on nonviolent, non-carceral ways to reduce violence and keep these communities safe.

Applying a public health approach to violence considered endemic to our society opens the door to alternative nonviolent solutions. Prevention can be focused on addressing roots causes—racial and other forms of trauma—and not just the symptoms—gun homicides and assaults. BIPOC communities face the legacies of decades of overincarceration and segregation into neighborhoods that do not have access to basic needs, such as clean water and adequate housing. It is likely that many incarcerated individuals would not have been imprisoned had they not lived in Adverse Community Environments. Meanwhile, being incarcerated increases one’s exposure to violence and then, upon release, makes it more difficult for an individual to find employment and therefore provide for one’s family or contribute to one’s community. Furthermore, the families of these incarcerated individuals are likely to face financial consequences of the criminal legal system in addition to the regular cost of living, not to mention the trauma of children growing up with missing parents and siblings. And the cycle of trauma, violence, and incarceration continues. The structural violence experienced by BIPOC communities contributes to the physical violence plaguing communities and societies across the U.S. It follows that reinforcing these cycles of trauma by further ensnaring BIPOC communities in the criminal legal system is counterproductive in curbing community violence.

People want to feel safe, and that is important. But there are more ways to achieve safety than by just over-policing and locking up BIPOC youth. These nonviolent approaches to violence prevention are not only more successful—they are less damaging in the process. Just as we advocate for ceasefires and diplomacy in global conflicts, so too should our city governments, and specifically offices of violence prevention, apply peacebuilding strategies in our own communities to keep civilians safe. [KP]

Questions raised

- How can city officials further integrate peacebuilding into city policy and programs, beyond programs focused specifically on violence prevention?

Continued Reading

Corburn, J., & Fukutome-Lopez, A. (2020). Outcome evaluation of Advance Peace Sacramento, 2018-19. UC Berkeley, IURD. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.advancepeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Corburn-and-F-Lopez-Advance-Peace-Sacramento-2-Year-Evaluation-03-2020.pdf

Peace Science Digest. (2021). Lessons learned from the law enforcement response to far-right terrorism.https://peacesciencedigest.org/lessons-learned-from-the-law-enforcement-response-to-far-right-terrorism-insights-for-a-more-effective-approach/

Organizations

Advance Peace: https://www.advancepeace.org/

Key words: gun violence, public safety, peace, healing, racism, violence prevention

Photo credit: Soupstock/ Adobe Stock