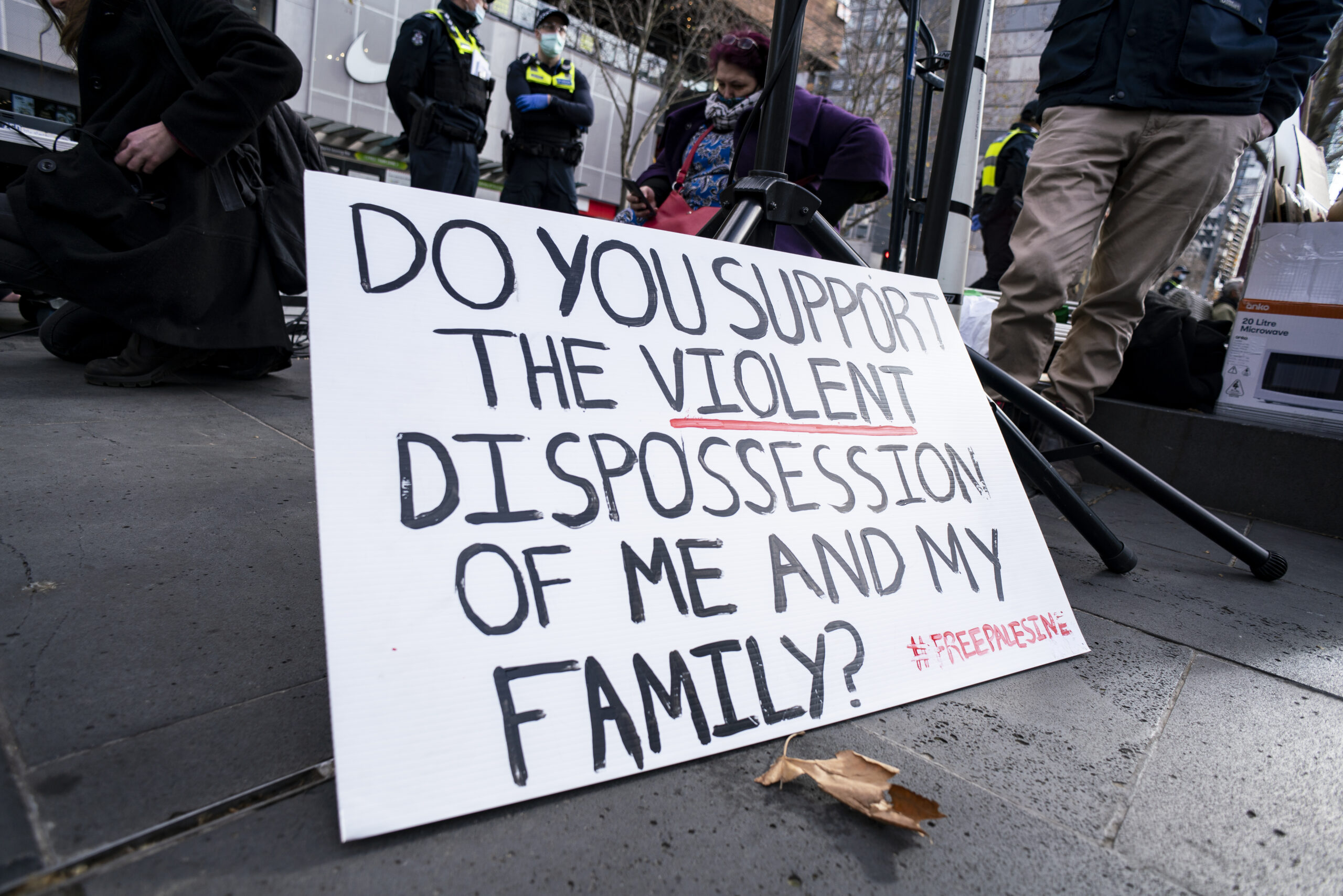

Photo credit: Matt Hrkac via flickr

This analysis summarizes and reflects on the following research: Gil-Glazer, Y. (2019). Photo-monologues and photo-dialogues from the family album: Arab and Jewish students talk about belonging, uprooting, and migration. Journal of Peace Education 16(2), 175-194.

Talking Points

- Photo-monologues and photo-dialogues were a useful educational tool to help Israeli and Palestinian students empathize with each other over shared familial trauma associated with migration to or from Israel.

- Migration is an important theme in the official education curriculum in Israel, but this curriculum emphasizes a Eurocentric view that marginalizes Mizrahi Jewish and Palestinian migration narratives.

- Photo-monologues and photo-dialogues drawing on family photos present “alternative public histories” that challenge official narratives on migration and help participants “reduce barriers” among various ethnic and religious identities in Israel.

Summary

“We all come from homes that have experienced significant pain involving migration. […] There is no real discourse in Israel about this, not many opportunities [to sit] in the same room talking—she about her Palestinian roots, me about my European roots.”

This quotation is from a participant in a series of workshops using photo-monologues and photo-dialogues to elicit discussion on belonging, uprooting, and migration. These are educational techniques that, through participants’ selection and presentation of family photos, encourage the blending of personal and political experiences, offering insight into different interpretations of historical events by those who experienced them. The author argues that the use of family photos, rather than official documentations of atrocities, does more to “reduce distances and bring people closer.”

| A photo-monologue | an educational technique where a student selects a still photograph and pairs it with “a quote by the person(s) in the photograph or someone who has a personal connection with [them].” |

| A photo-dialogue | an open-ended discussion built off the presentation of a photo-monologue. This technique is used to “constitute a treasure of testimonies on injustice…and thereby bring them to life […] by sharing and discussing them critically.” |

These photo-monologues and photo-dialogues were conducted over the course of four voluntary workshops among six female college students in arts and education in Israel. Two of the six were Arab—one Christian and one Muslim—and the remaining four were Jewish, one of Ashkenazi origin and the rest of mixed Ashkenazi-Mizrahi origin.[1] This represented a spectrum of ethnic and religious identities in Israel.

Employing photo-monologue and photo-dialogue techniques in Israel presents an opportunity both to “empathize with the suffering of others” across a range of ethnic and religious identities and to “archive alternative public histories.” In Israel, the official history curriculum selectively incorporates the theme of migration, excluding narratives of Mizrahi migrants and Palestinian refugees as part of an overall Eurocentric educational curriculum. Namely, the founding of the Israeli state is tied closely with the Holocaust and the influx of Jewish refugees from Europe in the late 1940s and 50s. Yet, the official curriculum excludes the Palestinian narrative which associates the establishment of the Israeli state with the “Nakba” (meaning catastrophe) wherein 700,000 Palestinians were expelled or fled from their ancestral homes and villages. Further, the migration of Mizrahi Jews is reported to be marginalized in the official curriculum by treating Mizrahi migration as adjunct to these events, entrenching the Eurocentric telling of history.

From the photo-dialogue workshops, the author identified three common themes across the presentations and discussions.

First, the trauma of migration was central to discussions, especially how it formed either an idealized past or an idealized future for the subject of the family photo. For stories that featured Holocaust survivors, migration to Israel and life thereafter were associated with happiness and hope. However, both Mizrahi Jewish and Palestinian presenters associated life before migration with happiness, with the subsequent migration to (Mizrahi) and from (Palestinians) Israel associated with pain and nostalgia.

Second, almost all of the presenters selected a photograph of their grandfather, noting that their grandfather’s migration narrative was central to the family’s narrative. For Palestinians, the grandfather figure represented “perseverance and adaption” and called for peace despite childhood experiences with war. For Jewish presenters, the grandfather represented a tragic figure who absorbed the pain of his past experiences and migration trauma to integrate into Israeli society.

Third, the themes of shame, concealment, and silencing were particularly prominent in the Palestinian and Mizrahi Jewish presenters. Mizrahi presenters described shame in their parents’ and grandparents’ identity crises following migration to Israel. They felt that they were treated as lesser than the European Ashkenazi Israelis. For Palestinians, their stories of the Nakba revealed “the huge gap between the Israeli curriculum and the Palestinians’ stories of migration, of which the Jewish students were completely ignorant.”

Participating in photo-dialogues led the participants to see their shared history of trauma associated with migration to/from Israel, albeit through dramatically different contexts and circumstances. Participants experienced critical breakthroughs, questioning the “unfounded hatred for the other side” and lack of engagement between Arab and Jewish communities prior to college. In conclusion, the author notes that this technique elevates the need to encourage personal-political discourse that involves a critical review of official education curriculum. Importantly, the use of family photos helps to reveal marginalized historical knowledge as an alternative to official narratives.

Informing Practice

Photo-monologues and photo-dialogues are one example of innovative approaches to interpersonal and intercommunal peacebuilding in deeply entrenched conflicts. In contexts like Israel and Palestine, where decades of conflict have alienated these communities, local approaches to peacebuilding can begin to challenge pre-conceived ideas and stereotypes that would otherwise inhibit dialogue between these groups. This is a particularly important task when official narratives on historical events advance an exclusive interpretation, rather than one that encompasses multiple sides of a given conflict. Jewish participants in these workshops reported no previous experience learning about the Palestinian forced migration (the Nakba). It wasn’t just exposure to Palestinian narratives of forced migration but the presentation of it through family photos that helped to bring participants of various ethnic and religious identities together. Sharing similar stories of migration and trauma helps to build a common understanding among participants.

As powerful as this example is, it is important to note incredibly disproportionate power dynamics between participants of various ethnic or religious identities in Israel. Helping to break down pre-conceived beliefs or stereotypes about the “other” is necessary to building peace but it does not, in and of itself, address the thorny political issues at the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Indirectly, efforts like these can begin to transform attitudes and beliefs which drive support for militarized solutions to the conflict. Within Israel, results of a series of elections this past year suggest deepening disagreement over the future direction of the country. The incumbent and conservative Likud Party, with Benjamin Netanyahu at the helm, failed to win a clear majority of the vote or achieve a governing coalition. The more moderate Blue and White Party, led by Benny Gantz, is mounting a considerable challenge to Likud Party rule, drawing a tie in the recent election. This loss for Likud came after Netanyahu promised to annex an additional 30% of the West Bank as a “security measure.” As this was a promise likely made to mobilize support, a possible interpretation of the Likud Party’s loss can be growing skepticism of an overtly militarized approach to security—skepticism that continued support for local peacebuilding initiatives can help to cultivate.

Continued Reading

Peace Science Digest. (2019, May). From encountering the “other side” to social change activism. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from https://peacesciencedigest.org/from-encountering-the-other-side-to-social-change-activism/

Peace Insight. (2014, December 31). Picturing peace: Using photography in conflict transformation. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from https://www.peaceinsight.org/blog/2014/12/photography-conflict-transformation-balkans/

DM&E for Peace. (2016, February 17). Using participatory photography for peace: A short guide for practitioners. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from https://www.dmeforpeace.org/resource/using-participatory-photography-for-peace-a-short-guide-for-practitioners/

Organizations

Sadaka-Reut: http://www.reutsadaka.org

Just Vision: https://www.justvision.org

Active Stills: https://www.activestills.org

Keywords: Israel/Palestine, migration, peace education, dialogue, peacebuilding

The following analysis appears in Volume 4, Issue 5 of the Peace Science Digest.

[1] Ashkenazi and Mizrahi are two sub-populations of the Jewish diaspora. The Ashkenazi diaspora settled throughout Europe whereas the Mizrahi diaspora settled throughout the Middle East and North Africa. Both diaspora groups emigrated to Israel following its statehood in 1948. Some Mizrahi populations were forced or fled to Israel from predominately Muslim countries.