This analysis summarizes and reflects on the following research: Combes, D. (2022). Counterinsurgency in (un)changing times? Colonialism, hearts and minds, and the war on terror. International Relations, 36(4), 547-567.

Talking Points

- Using the lens of time to analyze counterinsurgency (COIN) reveals its colonial heritage but also makes evident paradoxes and tensions within COIN doctrine that clarify why it repeatedly fails to serve U.S. interests.

- The central challenge for counterinsurgents is that they must distinguish between the “innocent masses”—to win over and protect—and the “supposedly dangerous and disposable few”—to capture or kill—when the line between the two can be nearly imperceptible, especially to outsiders.

- The uncertainty surrounding the “true” identity of the “Other” (civilian? insurgent?) makes it extremely difficult to ever end a COIN operation successfully because there could always be more insurgents to counter.

- COIN uses time paradoxically: It is presumed both to have an end-point—a point by which “hearts and minds” will have been won, which justifies COIN—and to be ongoing, since new insurgents could emerge at any time—leading to blurry temporal and geographical boundaries around COIN operations.

- Decoupling contemporary COIN from its colonial past hides the expansive, ongoing timeframe fundamental to how COIN was originally meant to function and instead permits COIN to be affixed with an expiration date that makes any “lasting victory” for the counterinsurgents unlikely if not impossible, as the insurgents just need to wait them out.

Key Insight for Informing Practice

- Knowing that we can never be perfectly safe—and that “our” violence in pursuit of security can actually exacerbate insecurity—U.S.-based antiwar activists and lobbyists should advocate for a more honest assessment of the timeframe and efficacy of military violence at the center of COIN and thereby create space to explore security-seeking tools that themselves instantiate the imperfect, life-giving world we wish to live in.

Summary

The U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 and the Taliban’s immediate return to power raises critical questions about the utility of military intervention, especially counterinsurgency (COIN). Using that moment as a jumping-off point, deRaismes Combes asks why COIN so frequently fails to end in military victory. By analyzing COIN through the lens of time, she reveals the colonial roots of COIN, as well as key contradictions at the heart of COIN doctrine that help explain its failure. Namely, COIN is presumed both to have an end-point (a point by which “hearts and minds” will have been won, which justifies COIN) and to be ongoing, since new insurgents could emerge at any time—leading to blurry temporal and geographical boundaries around COIN. Ambiguous time horizons favor insurgencies who can “bide their time,” making clear COIN victories difficult. The author sees her critique of COIN—which assesses its failures from the perspective of U.S. policy goals—as complementing postcolonial critiques by encouraging more reflection among COIN’s proponents.

| Counterinsurgency (COIN): | an approach to weakening an insurgency by not only fighting against insurgents but also disconnecting them from their non-combatant support base in the community. While military tactics are used to kill insurgents, political and economic tactics are used to “win hearts and minds” of community members and strengthen their connection with the government. |

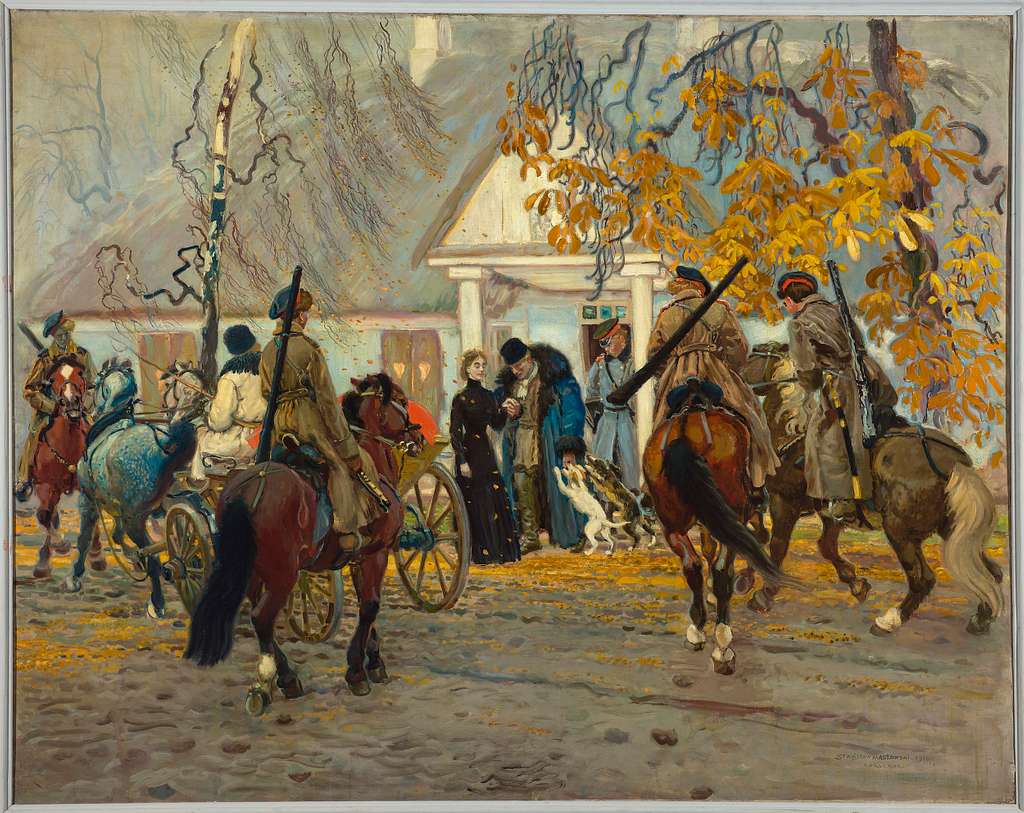

Tracing the history of counterinsurgency as a military doctrine, the author starts with the thinking of two 19th-century French generals who countered anti-colonial insurgencies: Bugeaud and Gallieni. Beyond military tactics, both recognized the importance of gaining the support of the civilian population by attending to livelihood and infrastructure needs and drawing on local governance structures and personnel. Close interactions between colonial forces and local communities then provided intelligence for military operations against insurgents. Both generals therefore saw military and political efforts as interdependent, as colonial counterinsurgency required, but could never fully gain, the support of the population—thus the need for military operations to nip any rebellion in the bud. Likewise, military control required more than violent tactics, so these were coupled with “bridge-building” (both literal and figurative) and other attempts to build “good will” among the populace.

Highlighting continuities across the 19th and 20th-21st centuries, the author notes that the U.S. wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq all eventually grew into counterinsurgencies, from the strategic provision of social services in Vietnam to gain “the good will of villagers,” and thereby access to and intelligence on Viet Cong, to the implementation of Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) in both Afghanistan and Iraq. Tracing COIN strategy from colonial times to the present reveals the through-line of cultural imperialism linking the so-called “civilizing mission” of colonialism with more recent discourses framing military occupation as somehow beneficial for a population through its transmission of democracy, human rights, free-market liberalism, and so on. These uses of violence in “service of civilization” also “create a never-ending need to subdue because the violence and exploitation inherent to pacification ultimately provokes resistance.”

Beyond revealing the colonial heritage of contemporary COIN, a temporal lens also exposes tensions within COIN doctrine that clarify why it repeatedly fails to serve U.S. interests.

First, a temporal lens reveals a central paradox related to “winning hearts and minds”: COIN is predicated on—and justified by—the assumption that hearts and minds can ultimately be won and the mission accomplished, but it also recognizes that not everyone can be won over, leaving open the possibility that insurgents may always remain, hiding among the population and thereby “requiring” ongoing COIN operations. The counterinsurgent must distinguish between the “innocent masses”—to win over and protect—and the “supposedly dangerous and disposable few”—to capture or kill. The difficulty is that it is incredibly hard for the counterinsurgent to distinguish between the two, as “the line between rebel and villager is paper thin.” Furthermore, notably, it is the counterinsurgent who “has the power to determine the Other’s identity” and make this distinction between “friend” and “enemy” that comes with life-or-death implications, robbing Afghans or Iraqis (for instance) of their own subjectivity and voice—and also “creating a permissive environment of violence” towards anyone deemed an “enemy.” Uncertainty surrounding the “true” identity of the “Other” therefore makes it extremely difficult to ever end a COIN operation successfully—to “move from ‘pacifying-time’ to ‘pacified-time’”—because more insurgents could always emerge.

Second, a temporal lens reveals another perspective on COIN’s contending time horizons. Linking contemporary COIN to its colonial past highlights how COIN was originally seen not as an aberration but as “unexceptional colonial ‘politics as usual’”—the sustained presence needed in the colony to reap the “material benefits of conquest.” Yet, today, military interventions, including COIN, are understood as “temporary and exceptional deviations”—with “expiration date[s], even if unspecified”—necessary to bring a country back to some “normal” Western ideal. Decoupling contemporary COIN from its colonial past hides the expansive timeframe fundamental to how COIN is meant to function—as an ongoing operation without an end-point. An expiration date, on the other hand, makes any “lasting victory” for the counterinsurgents unlikely if not impossible, as the insurgents just need to wait them out.

Informing Practice

Considering time horizons, as this research does, is a useful way for U.S.-based peace activists and lobbyists to reframe the narrative around military intervention on Capitol Hill and urge policymakers to closely examine and rethink their assumptions surrounding the use of military violence as a tool of foreign policy. When violence is justified as necessary or even moral action, it is typically done with reference to instrumental reasoning, as violence itself is (obviously) harmful, so it is only the purpose it is meant to serve that makes it appear (in some cases) acceptable. Yet, if the end is what justifies military means, how soon must that end come to fruition for us to determine that those means are an acceptable price to pay? If those ends are, instead, ever elusive, always slipping further and further into the future, at what point can we determine that the means are not actually serving the ends intended? That all we have to show for the war effort are human casualties, destroyed infrastructure and communities, and further entrenched polarization and grievance?

Furthermore, the critical reframing that emerges from these questions is only strengthened when we consider, again as this research does, that the military components of COIN may not only be ineffective at bringing about a particular end goal in a certain amount of time but may also actively work against that desired end goal. If, as noted above, “the violence and exploitation inherent to pacification ultimately provokes resistance,” it makes even less sense to employ military tools to create security. This is an additional paradox at the center of COIN: The two dimensions of COIN—”winning hearts and minds” and military violence against those who will not be won—that are meant to be complementary are ultimately at odds. For every heart or mind that is gained through a development project, there is another lost when a brother or father is killed in a nighttime raid of a presumed insurgent hideout—with military operations actually reproducing the pool of insurgents they are meant to eliminate by further alienating people and creating the understandable grievance that comes of military occupation. Additionally, if we think of security as broader than safety from threatened or actual direct violence—also including basic general well-being including access to food, shelter, and healthcare—we can see how the military dimensions of COIN can exacerbate insecurity in this way as well, as the destructiveness of war counters gains in socio-economic well-being. Instead of creating security, then, the military dimensions of COIN can actually generate ever greater vulnerability for insurgents and counterinsurgents alike, not to mention the “innocent masses” that COIN forces are meant to protect.

Carol Cohn, drawing on Sara Ruddick’s “maternal thinking” as a lens for thinking about international security, reminds us that we can never be perfectly secure. No matter how massive our military budget or how technologically advanced our weaponry or how high our walls, we are still vulnerable. While mainstream defense intellectuals may take this inescapable vulnerability as further motivation and justification for never-ending militarization and “forever war”—the Sisyphean task of trying to reach a state of perfect security through complete control of one’s environment—acknowledging our fundamental vulnerability can also take us in the other direction, leading us to reconsider whether this unsatisfying “end”—still vulnerable, never perfectly secure—can ever be worth all the human and material costs of military intervention.

The case of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Afghanistan brings these points home. Nearly twenty years after the U.S. invaded Afghanistan to rout the Taliban (to deny al-Qaeda “safe haven” and also, putatively, to stop its oppression of women), when the U.S. withdrew its forces from Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban promptly returned to power and tamped down women’s rights once again. The difference was that, between 2001 and 2021, over 176,000 people (on all sides, combatants and non-combatants), including over 46,000 Afghan civilians, lost their lives as a direct result of the violence of the war and occupation. Taking a broader view of security, according to a report from the Costs of War Project, whereas 62% of Afghans faced food insecurity before the U.S. invasion in 2001, 92% did as of 2022. Likewise, acute malnutrition was experienced by 9% of children under five in 2001 and by 50% of them in 2022, and overall poverty levels went from 80% to 97% between 2001 and 2022.

Knowing that we can never be perfectly safe—and that “our” violence in pursuit of protection and security can even actually exacerbate insecurity, both further direct violence and broader forms of insecurity—let’s advocate for a more honest assessment (and, ultimately, abandonment) of the military violence at the center of COIN, with its promises of some distant perfect security that will never materialize. By doing so, we create the space to explore instead security-seeking tools that in and of themselves—means as “ends-in-the-making”—instantiate the imperfect, life-giving world we wish to live in. [MW]

Questions Raised

What would it mean to take more seriously how our adversaries define themselves, rather than foisting identities (like “insurgent” or “civilian”) on them? How would this change our understanding of the conflicts we’re involved in, the motivations of our adversaries, the movement and permeability between “civilian” and “insurgent” categories, and the il/legitimacy of our own presence?

If “combatants/insurgents” and “non-combatants/civilians” are not static or mutually exclusive categories, how do different forms of security-seeking interventions influence the movement of individuals from one category to the other?

What sorts of interventions or actions, when judged by the reality they enact now rather than by the reality they are meant to bring about eventually, cultivate security without trying to control it? If means are “ends-in-the-making,” which security-seeking tools in and of themselves also reflect the reality we wish to create?

Continued Reading

Costs of War Project. (2022). Afghanistan before and after 20 years of war (2001-2021). Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs. Retrieved June 30, 2023, from https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/Afghanistanbeforeandafter20yearsofwar

Costs of War Project. (2021). Human cost of post-9/11 wars: Direct war deaths in major war zones. Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs. Retrieved June 30, 2023, from https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2021/Costs%20of%20War_Direct%20War%20Deaths_9.1.21.pdf

Network of Concerned Anthropologists. (2009). The counter-counterinsurgency manual: Or, notes on demilitarizing American society. Prickly Paradigm Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/C/bo6899695.html

Lake, D. (2021, August 17). Why statebuilding didn’t work in Afghanistan. Political Violence at a Glance. Retrieved July 10, 2023, from https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2021/08/17/why-statebuilding-didnt-work-in-afghanistan/

United Nations. (2023, May 5). Afghanistan: Women tell UN rights experts ‘we’re alive, but we’re not living’. UN News. Retrieved July 12, 2023, from https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/05/1136382

McCarthy, E. (2021, August 24). What a truly humanitarian response in Afghanistan would look like. Waging Nonviolence. Retrieved July 10, 2023, from https://wagingnonviolence.org/2021/08/what-a-truly-humanitarian-response-in-afghanistan-would-look-like/

Cohn, C. (2014). Cohn, C. (2014). “Maternal thinking” and the concept of “vulnerability” in security paradigms, policies, and practices. Journal of International Political Theory, 10(1), 46-69. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1755088213507186?casa_token=CYZkp0JFG54AAAAA:Co0sLydjCid-GFbfc062Q6DchnHVKiXKWxlYDasHHsPZ0EdgwOD2PZ-PGXPTuuoOd_u7mO6Vif-5

Ruddick, S. (1995). Maternal thinking: Toward a politics of peace. Penguin Random House. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/203968/maternal-thinking-by-sara-ruddick/

Organizations:

Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan: http://www.rawa.org/index.php

Friends Committee on National Legislation: https://www.fcnl.org/

CodePink: https://www.codepink.org/

Win Without War: https://winwithoutwar.org/

Key Words: managing conflicts without violence, counterinsurgency, Afghanistan