We are pleased to present our special issue on the relationship between local, national, and international peacebuilding in partnership with Peace Direct. The recent reorientation towards local peacebuilding represents a radical shift in whose voices are centered in the work of creating a more peaceful and just world. The grievances that lead to war are rarely, if ever, addressed through violence. Instead, after war these grievances persist, joined by the immeasurable loss of human life and the all-encompassing trauma, fear, polarization, and neglect that violence begets. When countries emerge from war, the very act of peacebuilding constitutes a rethinking of the social and political problems that gave rise to these grievances. It matters, therefore, that decision-making power in peacebuilding rest with those directly affected by these problems and their potential solutions.

Local peacebuilding can be a powerful force for change by centering local expertise and solutions, creating space for marginalized voices to lead, and shifting resources, economic or otherwise, to local agents of constructive change. Local ownership makes peace stick. The broader peacebuilding field has recognized and embraced this “turn” to supporting local peacebuilding, but this shift also presents a new set of challenges and considerations. For instance, how should international peacebuilders contend with national politics while engaging with local communities? How can donors be persuaded to hand over substantial decision-making power to local communities about the goals and activities of the programs they fund? How might the “local turn” fundamentally reshape some of the bedrock assumptions international peacebuilders make about peacebuilding practice and their own role in peacebuilding?

To unpack these complex relationships among local, national, and international scales in peacebuilding, we have curated analyses on five academic articles that investigate what is meant by—and contestation within—the “local” (Obradovic-Wochnik, Piccolino), how unequal value is attributed to international versus local peacebuilding knowledge (Autesserre, Goetze), and how relationships between international and local peacebuilders influence peacebuilding outcomes (Boege & Rinck). At the core of all these conversations is the question of power—who has it, who can wield it, and how does it ultimately shape political institutions in post-war societies? By questioning who the “local” is, the analyses point out that national elites can drown out less powerful voices or enforce a “victor’s peace” that may fail to address root causes of violence. Examining the hierarchy between international and local peacebuilding actors reveals that local perspectives on peace are often marginalized in the larger field of peacebuilding while international actors’ experiences and assumptions are privileged. Taking into account both of these questions, the final analysis examines how the nature of relationships between international and local actors can fundamentally shape peacebuilding processes and outcomes, including those related to security and reconciliation.

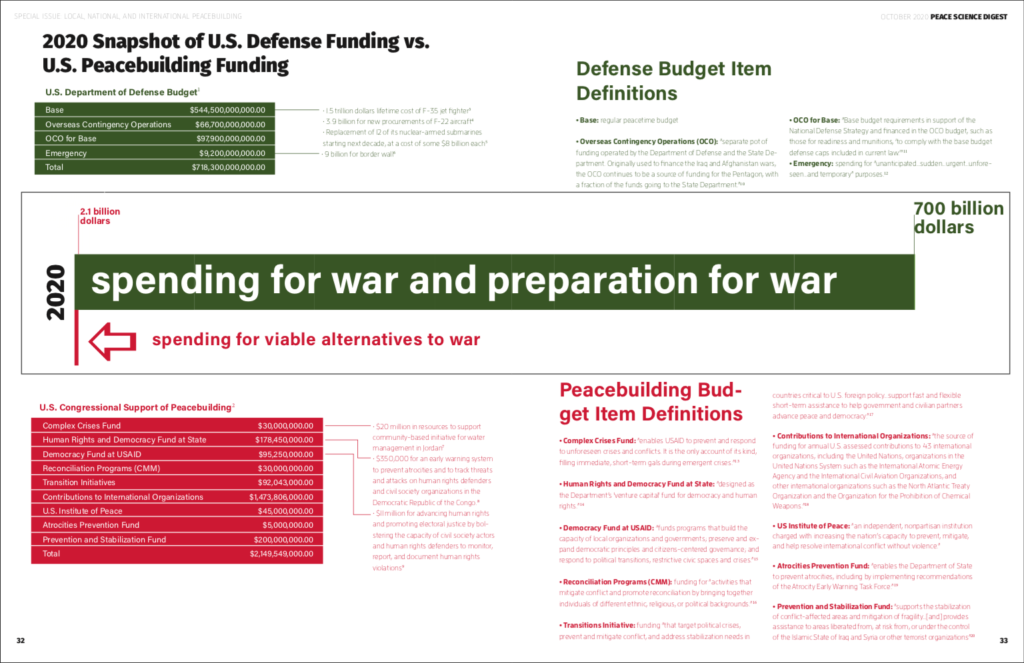

As much as the “local” may be increasingly recognized as a source of peacebuilding expertise and activity, we cannot escape the broader context of militarization within which local peacebuilding takes place. Local peacebuilders do an incredible amount with very little. How much more could become possible if societies decided to devote the resources they currently devote to the military to peacebuilding efforts? We end this special issue with a clear message: Military spending undercuts efforts to build peace. Rather than bring security, militarized approaches to conflict not only create direct harm but also pull resources from schools, health and trauma care, vocational training, housing, food security, sustainable energy, reconciliation work, arts and culture, and so on—all of which, with ample resources, would actually make individuals and communities more secure, more vibrant, and more resilient, especially after years of armed conflict.

- Recognizing the Hidden Politics of Local Peacebuilding

- The Link Between Local- and National-level Peacebuilding After Military Victory

- The Role of Assumptions in Shaping International Support of Local Peacebuilding

- Local knowledge Disparaged in Peacebuilding

- The Important of Local/International Relationship-Building to Peacebuilding in Bougainville and Sierra Leone