As we reflect on the genocidal violence enacted on Palestinians in Gaza over the past two years, and now the Pentagon’s heinous bombing campaign against Venezuelan boatmen, it becomes evident that racism plays a central role in enabling such military violence. This month’s round-up examines race and racism within the peace and security field.

What We’re Reading

For each of the articles mentioned below, we include the central research question and the authors’ main findings:

1) Capella, M. (2024). Whose norms and whose peace? A critical analysis of counterprotests against an Indigenous-led mobilization in Ecuador. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 30(3), 472-481.

In the context of Indigenous-led anti-government protests and counterprotests in Ecuador in 2022, “[h]ow did counterprotesters’ discourses about peace reproduce or challenge existing power asymmetries in Ecuador?”

- The counterprotesters’ discourses framing the Indigenous-led protests as violent, and framing their own response as peaceful and as defending democracy and law and order against the chaos and disruption of the anti-government protesters, ultimately reinforced “liberal notions of peace” and “historical power asymmetries.”

- For counterprotesters, “violence” was a term reserved for “threats to liberal peace,” including “disruption” (“visible confrontation that significantly disrupts and convulses everyday life”), “radicalization” (making demands and refusing dialogue), and “destruction.”

- For Indigenous-led, anti-government protesters, the liberal peace that counterprotesters were defending was itself a violent order that needed changing—hence their demands that “focused on unmet rights and issues of structural violence.”

- While counterprotesters were focused on avoiding direct violence, anti-government protesters were focused on struggling against direct, structural, and cultural violence.

- Embedded in the counterprotesters’ norms and behaviors were three contradictions of liberal peace: selective enforcement of the emergency measures in favor of the congregation of counterprotesters but not of Indigenous-led anti-government protesters; legitimizing or celebrating police or counterprotester violence and/or destruction while condemning that of anti-government protesters; and “the paradox of demanding dialogue through legal coercion” and protest.

- On the whole, mainstream media echoed the counterprotester discourse, adopting the framing that counterprotesters were “defenders of liberal peace” against “violent antigovernment protesters.”

2) Palmiano Federer, J. (2024). Diversity, equity, and inclusion for peace? Making visible epistemic exceptionalism in peacebuilding discourse. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 53(1), 113-135. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298241288493

This article brings together decolonial studies and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in a critical assessment of Global North peacebuilding research, discourse, and practice.

- Peacebuilding institutions located on Turtle Island (an Indigenous term for the North American continent) have not applied a DEI framework to the “systems of structural oppression and racism in [their] own context, instead promoting inclusive peace in conflicts ‘over there’,” often meaning in the Global South.

- The author proposes the concept of “epistemic exceptionalism”—as a form of epistemic violence—to explain how the peacebuilding field has “bypassed and silenced” a “real discourse around DEI” to ignore various forms of violence against Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) on Turtle Island.

- The peacebuilding field acts as “an arbiter…around what counts and does not count as a conflict” where the dominant definitions of war and conflict “obfuscate police brutality and other forms of structural oppression experienced by marginalized and oppressed groups in Turtle Island.”

- The peacebuilding field lacks self-reflection in its research and practice where greater self-reflection could lead to “reframing conflict beyond the parameters of ‘battle deaths’ towards something structural, oppressive, and born out of coloniality.”

- The author reviews the mission and value statements of several top peacebuilding and conflict resolution organizations and reveals that DEI is reduced to a box-ticking exercise focused on promoting “inclusion within their organizational cultures and the inclusion agenda as a peacebuilding normative agenda to promote abroad.”

- The proposed alternative is to “broad[en] and reimagin[e] mainstream definitions and conceptual understandings of [terms] such as ‘conflict’ or ‘peace’.” For instance, “conflict resolution NGOs can play a critical role by broadening their areas of conflict analysis and programming to instances of violence and conflict in the Global North, for instance, ongoing and structural incarceration and police brutality against Black communities in the United States, or the crisis of violence against Indigenous women and girls in Canada.”

Key terms

|

Epistemic violence: |

The marginalization or exclusion of particular ways of knowing or forms of knowledge. |

3) Mesok, E., Naji, N., & Schildknecht, D. (2024). White supremacy and the racial logic of the global preventing and countering violent extremism agenda. Third World Quarterly, 45(11), 1701–1718. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2024.2370358

How does the (performative) rejection of explicit forms of white supremacist violence reveal rather than disrupt the white supremacist logics underpinning the P/CVE and global security agenda?

- The global preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE) framework is underpinned by racialized concepts (designed to target Muslim populations) such as “prevention,” “radicalization,” and “community.”

- Within the P/CVE framework, “other” (non-white) communities are seen as risky and more susceptible to having extremist views (being radicalized), thus needing to be surveilled as a means of “preventing” violence—this is conceptualized specifically with Muslim populations (globally) in mind.

- P/CVE has become a “thingified” concept—abstract ideas (like radicalization or extremism) are treated as fixed objects that can be acted upon by the security sector, which allows for actors and donors to flexibly (re)define and use P/CVE language for political and funding purposes.

- The inclusion of white supremacist violence within domestic counterterrorism policy (especially in the U.S.) functions as a disavowal—a way to rhetorically distance liberal democracy from overt racism without addressing its structural foundations.

- The U.S. strategy of naming white supremacy as a domestic threat is more symbolic than it is transformative.

4) Fourie, M. M., Deist, M., & Moore-Berg, S. L. (2022). Hierarchies of being human: Intergroup dehumanization and its implication in present-day South Africa. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 28(3), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000616

Does the racial hierarchy created under apartheid still shape how South Africans perceive each other’s humanity today, and how do these perceptions influence intergroup relations and support for structural reform?

- Old hierarchies still shape attitudes: Even decades after apartheid, people’s views about who is “more human” still follow the old racial order: White > Coloured (lighter toned individuals who are still not considered “white”: see colorism) > Black African.

- Dehumanization is widespread: People from all groups show some level of dehumanization toward others, but it is strongest from those with more social power toward those with less.

- Feeling dehumanized makes things worse: If you feel like another group sees you as less than human, you are more likely to see them that way too. This creates a cycle of negative attitudes.

- Belief in hierarchies matters: People who believe some groups are naturally better than others are more likely to dehumanize others and support policies that keep things unequal.

- Positive contact helps: Having good, meaningful interactions with people from other groups can reduce dehumanization.

- Dehumanization inhibits desire for social change: For White participants, dehumanizing Black Africans predicted wanting more social distance, less support for protests for equality, and more support for policies that maintain the status quo.

Informing Practice

Is the U.S. on the verge of a new war with Venezuela? Amid a military build-up along Venezuela’s coastline and the unlawful and inhumane executions of civilians—even if they are indeed traffickers—in the Caribbean, the march to war appears to be in full swing. The desensitization and normalization of mass murder of non-white bodies—from the prolonged Vietnam War to the Global War on Terror and the devasting military invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq to unquestioned military assistance in support of the genocide in Gaza—is the consequence of what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., described as the “triple-prong sickness that has been lurking within our body politic from its very beginning. That is the sickness of racism, excessive materialism, and militarism.” It relies on Western media’s long-term efforts to frame non-white bodies as less important, disposable, or subhuman through racist and white supremacist lenses. Violent, militaristic racism flourishes in U.S. foreign and national security policy. Today, civilians on boats are the immediate victims while a larger, entrenched, forever war project looms on the horizon on the Venezuelan mainland.

Racism not only produces non-white bodies as less human and more disposable, but it also casts predominantly non-white populations as unfit to problem-solve or govern themselves and therefore in need of foreign (predominantly White/Western) intervention. And Empire often co-opts—through elite capture and tokenism—individuals from minority backgrounds to affirm and further its own imperial, racist agendas. It should be a bright red flag that a recent Noble Peace Prize winner, Maria Corina Machado, would welcome U.S. strikes on civilian boats, as well as a military build-up in the Caribbean. Militarism is a threat to democracy. The many failed attempts at externally imposed regime change by the U.S. government, including the long history of destructive meddling by the U.S. in Latin America, ought to put an end to any fantastical idea that it is the right thing to do.

The immediate course of action is to strongly oppose and work towards preventing a forever war in Venezuela, while seeking accountability for the strikes that have illegally killed dozens of the civilians. The U.S. military’s ongoing bombing campaign of everyday Venezuelans should be strongly rebuked—and the idea that the U.S. can act as the judge, jury, and executioner within international affairs should be challenged and dismantled. The long-term, generational effort lies in uprooting the “sickness” of racism and militarism in U.S. foreign and national security policy—let alone from the total “body politic” of the country. The research reviewed in this month’s round-up offers several pathways to do so.

Examining how the term “peace” is used in mainstream discourses, especially to reinforce existing power relations (Capella), provides a valuable avenue for critical scrutiny of how society is organized—especially whose peace is valued and whose is disregarded. Furthermore, the idea of epistemic exceptionalism (Federer), by which institutions situated in the Global North see themselves as exceptions—thereby externalizing conflict and violence as something that happens “elsewhere” but not at home—erodes possibilities for reflective thinking and effective resistance against the domestic State that seeks to entrench its powers by “progressively” militarizing and surveilling its local populace. In the context of the United States, it is worthwhile to interrogate who benefits, who is at risk, and who is simply excluded from its “imagined community”? What does it mean for a nation to prioritize bombs over feeding its own people?

The notions of “positive peace” and “negative peace,” as posited by Johan Galtung in 1969, are helpful in conceptualizing variations of “peace.” Negative peace is the absence of war and physical violence, whilst positive peace is that plus the presence of justice. In post-apartheid South Africa, dehumanizing attitudes toward non-white people persist (Fourie), and unequal access to education, unequal pay, segregated communities, and massive economic disparities remain a reality—one that is reinforced by existing institutions of colonial legacies. Similar experiences can be accounted for by Black Americans who have endured a legacy of slavery in the U.S., while Arab (and Muslim) Americans, particularly since the 2001 Global War on Terror (GWOT) and Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (P/CVE) agenda, which are built on white supremacist foundations (Mesok et. al), experience ever-increasing policing. Whose norms and whose peace do we then uphold (Capella), within our attempts to be “civil,” to a system that is designed to oppress and privilege certain peoples over others—and how can we be complicit in maintaining these systems of structural violence, by our preemptive and continuous compliance, and even our servitude to it?

The solutions to the woes of systemic violence and oppression—and by extension of colonial and white supremacist legacies—cannot come from the same logics that have entrenched us in this position. Efforts grounded in anti-racist and decolonial principles, that are led by Indigenous peoples, women’s groups, and others who are most directly impacted by legacies of colonial violence, should be supported and enacted through policy and structural reforms. On an individual level, efforts to decolonize the mind, resist the normalization/desensitization of state violence, show up in solidarity and community with groups that are most impacted, and efforts to amplify their narratives must go in tandem with larger systemic changes.

Recommended Reading:

Rickford, R. (2017, February 24). Malcolm X and anti-imperialist thought. African American Intellectual History Society. https://www.aaihs.org/malcolm-x-and-anti-imperialist-thought/ (AAIHS)

Byrd, D. J., & Miri, S. J. (Eds.). (2023, November). Syed Hussein Alatas and critical social theory: Decolonizing the captive mind (Studies in Critical Social Sciences). Haymarket Books. ISBN: 9798888900185. https://www.haymarketbooks.org/books/2139-syed-hussein-alatas-and-critical-social-theory (haymarketbooks.org)

War Prevention Initiative. (n.d.). Racism as a foundation of the modern world. Peace Science Digest. https://warpreventioninitiative.org/peace-science-digest/racism-as-a-foundation-of-the-modern-world/ (warpreventioninitiative.org)

Booker, S., & Ohlbaum, D. (2021, September). Dismantling racism and militarism in U.S. foreign policy (Discussion paper). Friends Committee on National Legislation Education Fund. https://www.fcnl.org/dismantling-racism-and-militarism-us-foreign-policy (fcnl.org)

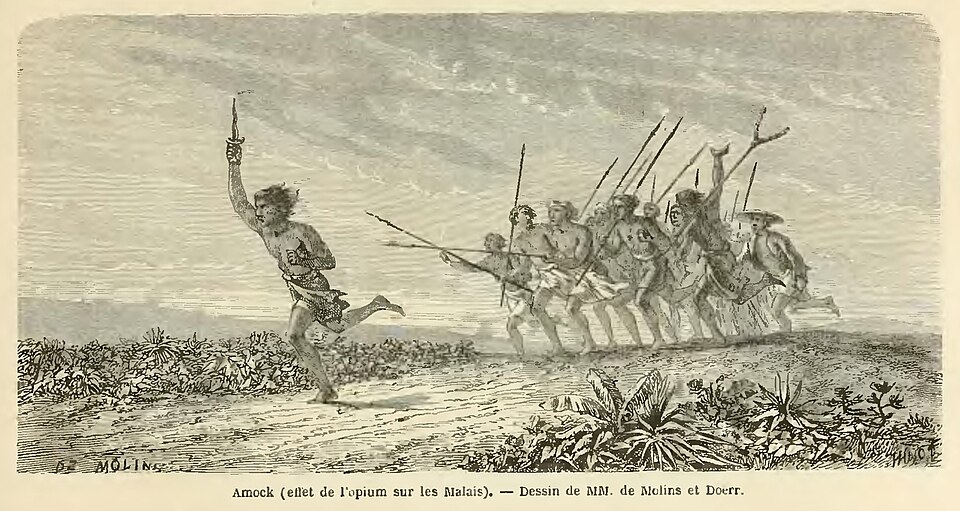

Photo credits: Wikimedia Commons