Citation: Silverman, D., Kent, D., & Gelpi, C. (2022). Putting terror it its place: An experiment on mitigating fears of terrorism among the American public. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 66(2), 191-216. DOI: 10.1177/00220027211036935

Talking Points

Based on the results of a nationally representative survey:

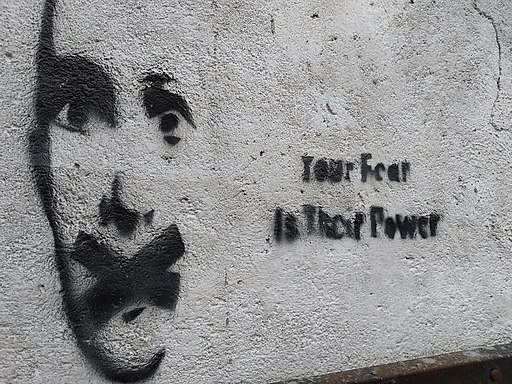

- Americans’ fears about the risks of terrorism are overinflated, leading to an “aggressive response to the threat.”

- Facts about the risk of terrorism, especially in the context of other risk factors, can mitigate Americans’ fears of terrorism and bring them into closer alignment with reality.

- While there are some differences between Republicans and Democrats, survey respondents of both party affiliations were willing to change their beliefs about terrorism when provided with facts.

Key Insight for Informing Practice

- Toxic polarization in the U.S. makes it exceedingly more difficult for facts to change Americans’ mind—especially on national security and foreign policy issues where Republicans and Democrats disagree—but peacebuilding can rein in polarization to support political change.

Summary

Americans face a 1 in 3.5 million yearly chance of being killed in a terrorist attack—whereas the risk of death from “cancer (1 in 540), car accidents (1 in 8,000), drowning in a bathtub (1 in 950,000), and flying on a plane (1 in 2.9 million) are all greater than terrorism.” Yet, Americans tend to believe that terrorist attacks are likely to occur and worry about whether loved ones may become victims of terrorism. As such, fears about terrorism are overinflated in the U.S., leading to an “aggressive respons(e) to the threat…fueling the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, [ballooning the] country’s defense budget [and] homeland security apparatus.”

Daniel Silverman, Daniel Kent, and Christopher Gelpi explore what can change Americans’ views on terrorism so that they are better aligned with the actual risks and thereby “reduce [the] emphasis on terrorism as a national security threat and [the] demand for policies to counter it.” The authors conducted a nationally representative survey and found that Americans change their beliefs about the risks of terrorism when presented with facts about the risks of terrorism in the context of other risks. Remarkably, the authors observed a significant drop in the number of Americans reporting fears about terrorism as result of their survey and found that these new beliefs were maintained two weeks after taking the survey.

Previous research has found that Americans’ exaggerated response to terrorism is considered a “bottom-up phenomenon,” meaning that American political elites are not creating elevated fears as much as they are responding to demands from the public. Biased news coverage on terrorism has, however, likely contributed to overinflated fears. For example: “terrorist attacks accounted for less than 0.01 percent of deaths in the United States, yet nearly 36 percent of the news stories about fatalities that appeared in the New York Times in 2016 were about deaths from terrorism.” However, there is existing evidence to suggest that Americans will update their beliefs when presented with facts. Previous research has found that Americans often respond rationally to new information about foreign policy and correct false beliefs on a range of policy issues when presented with facts. Further, evidence suggests that citizens change policy beliefs when new information is supported by “trusted elites” or if there is “elite consensus behind a specific foreign policy stance.”

The authors designed a survey experiment to test how Americans respond to accurate information on the risks of terrorism and whether that information is endorsed by Republicans, Democrats, or the U.S. military. In May 2019, a total of 1,250 American citizens participated in the survey, and all participants read a story “about a recent terrorist attack that mirrored the general discourse around terrorism in the country and reinforced public concern.” A control group—meaning, a smaller, random grouping of the 1,250 survey participants who were not presented with accurate information on the risks of terrorism—only read the story about the terrorist attacks. Four other random groupings of survey participants were presented, in addition to the story, with information on the actual risks of terrorism: One group received only risk statistics, and the remaining three groups received risk statistics that were endorsed by a political elite (either a Democratic congressperson, a Republican congressperson, or a senior military officer). After reading these stories, survey participants were asked to review and rank the importance of various national security concerns and foreign policy goals.

After running a series of statistical tests, the authors found that Americans’ risk perceptions of terrorism went down significantly when they were given accurate information. Among the group given risk statistics without elite endorsement, the authors observed a 10-percentage-point drop in respondents’ “perception of terrorism as an important national security and foreign policy priority.” This finding was twice as large a drop as that found with groups receiving risk statistics that were endorsed by a political elite, suggesting that “[facts] about terrorism [are] more important than whether it comes with an elite endorsement.” While they found slight differences between survey respondents who identified as Republican or Democrat—for example, Republicans were more likely to rank terrorism as a national security threat and foreign policy priority—the authors found overall that members of both parties were willing to change their beliefs about terrorism. A two-week follow-up survey showed that respondents’ updated beliefs about the risk of terrorism were maintained, meaning respondents rated terrorism as a national security threat and foreign policy priority at similar rates to the first survey results.

These results point to the possibility that “much of the vast overreaction to terrorism in the U.S…. might have been avoided [if] citizens were given a more accurate picture of the threat and the risks it poses to them.” The authors caution that their experiment alone—a one-time exposure to the actual risks of terrorism—cannot drive lasting change and that “a sustained shift in public discourse” would be necessary to support change. For example, they point to media, noting previous empirical evidence calling out the media for vastly exaggerating the risk of terrorism. However, the authors are optimistic, as their results demonstrate how Americans’ views on terrorism can be better aligned to the actual risks.

Informing Practice

The central argument of this research is that facts can actually change beliefs. The question of whether facts can change beliefs came into sharp focus in the aftermath of the 2016 U.S. Presidential election with Donald Trump’s win and the introduction of “alternative facts.” Much of the liberal discourse at the time landed on the answer that facts (alone) cannot change minds—like this popular New Yorker piece Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds—as a way to explain how someone who so clearly lies like Donald Trump could possibly become president. The truth is more complicated. In their discussion, Daniel Silverman and his co-authors point to research by Alexandra Guisinger and Elizabeth N. Saunders finding that “a key driver of the correctability of misperceptions on foreign policy issues is the extent to which they are politicized across partisan lines.” Observing only mild differences in beliefs around the risk of terrorism along partisan lines in their sample, Silverman et al. refer to Guisinger and Saunders’ research to caution about the applicability of their findings to more “politically polarized” foreign policy issues.

However, this relatively minor discussion point in Silverman et al.’s research holds huge implications for the ability of facts to change beliefs in a highly polarized political environment, like today’s U.S. To be clear, polarization itself is not necessarily bad—rather, it is “a necessary and healthy aspect of democratic societies.” Polarization is an important tool for activists as it helps to energize and mobilize citizens to advocate for political change. What’s dangerous in the U.S. is the rise of toxic polarization, or “a state of intense, chronic polarization—where there are high levels of contempt for a person’s outgroup and love for one’s own side,” according to resources compiled by the Horizons Project. Research from Beyond Conflict quantifies toxic polarization in the U.S., finding that both Republicans and Democrats dramatically overestimate how much the other party dehumanizes, dislikes, and disagrees with them.

We can safely postulate that the prevalence of toxic polarization may lessen the potential of facts to moderate views about national security and foreign policy. In 2018, the Pew Research Center identified several foreign policy issues where Democrats and Republicans held significantly different views, including refugees and immigration, climate change, trade, and foreign relations with Russia, Iran, China, and North Korea. Decisions in any of these policy areas have the potential to directly benefit or directly harm millions (if not the entire world).

So, what can be done to produce healthy polarization—which humanizes political opponents without sacrificing support for systems change—and, likewise, an environment where facts can be influential in changing beliefs? In May 2021, the Horizons Project brought together peacebuilders and activists to answer a similar question. They note that dialogue alone cannot solve the problem of toxic polarization. Rather, they emphasize humanizing the other by building bridges among different identity groups and strengthening existing community-based structures where Republicans and Democrats co-mingle.

This is not to suggest that the severity of toxic polarization in the U.S. is equally driven by both sides—that a Republican lawmaker can refer to all Democrats as pedophiles without any consequences is insane—but rather that everyone has a role to play in reining in toxic polarization so we can create the conditions where facts can influence opinion again. [KC]

Continued Reading

Beyond Conflict. (2022, June). America’s divided mind: Understanding the psychology that drives us apart. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://beyondconflictint.org/americas-divided-mind/

Guisinger, A. & Saunders, E. N. (2017, June) Mapping the boundaries of elite cues: How elites shape mass opinion across international issues. International Studies Quarterly, 61(2), 425-441. https://academic.oup.com/isq/article/61/2/425/4065443.

Horizons Project. (n.d.) Good vs. toxic polarization. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from, https://horizonsproject.us/resource/good-vs-toxic-polarization-insights-from-activists-and-peacebuilders/

Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2019). How democracies die. Penguin Random House. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/562246/how-democracies-die-by-steven-levitsky-and-daniel-ziblatt/

Peace Science Digest. (2022). Awareness of the specific harm caused by nuclear weapons reduces Americans’ support for their use. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://warpreventioninitiative.org/peace-science-digest/awareness-of-the-specific-harm-caused-by-nuclear-weapons-reduces-americans-support-for-their-use/

Peace Science Digest. (2017). In nuclear disarmament campaigns, the messenger matters. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://warpreventioninitiative.org/peace-science-digest/nuclear-disarmament-campaigns-messenger-matters/.

Peace Science Digest. (2017). Peace journalism and media ethics. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://warpreventioninitiative.org/peace-science-digest/peace-journalism-and-media-ethics/

Pew Research Center. (2018, November 29). Conflicting partisan priorities for U.S. foreign policy. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2018/11/29/conflicting-partisan-priorities-for-u-s-foreign-policy/

Saleh, R. (2021, May 25). Good vs. toxic polarization: Insights from activists and peacebuilders. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://horizonsproject.us/good-vs-toxic-polarization-insights-from-activists-and-peacebuilders-2/

Organizations

Horizons Project: https://horizonsproject.us

Beyond Conflict: https://beyondconflictint.org

Peace Voice: http://www.peacevoice.info

Media Matters: https://www.mediamatters.org

Keywords: terrorism, GWOT, demilitarizing security

Photo credit: Wikipedia