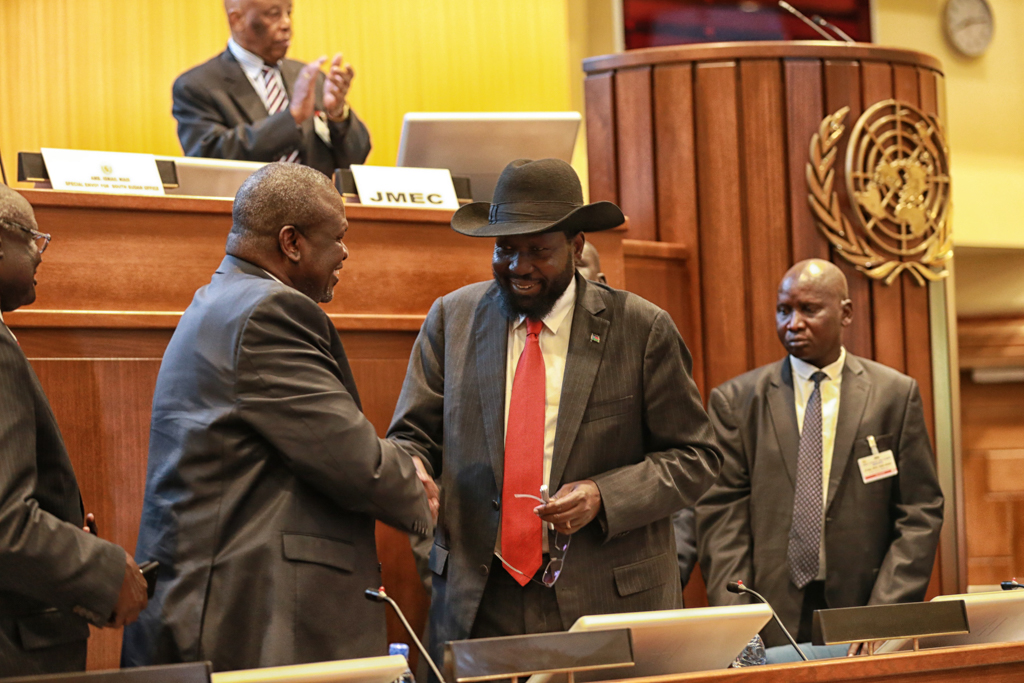

Photo credit: UNMISS via flickr

This analysis summarizes and reflects on the following research: Lounsbery, M. O., & DeRouen, Jr., K. (2018). The roles of design and third parties on civil war peace agreement outcomes. Peace & Change, 43(2), 139-177.

Talking Points

- More complex peace agreements with a greater number of provisions correspond with a greater probability of failed implementation and of armed conflict recurrence.

- Simpler peace agreements with fewer provisions are more likely to be successful at preventing armed conflict recurrence.

- Armed intervention in support of the government and mediation both correspond with more comprehensive peace agreements.

- Armed intervention in support of rebel forces and sanctions correspond with less comprehensive peace agreements.

Summary

Since the 1970s, civil wars have become an increasingly prevalent form of violent conflict. Much attention has been devoted to improving the design of peace agreements intended to resolve these conflicts. Important questions still remain, however, about how comprehensive these peace agreements should be. Some suggest that more elaborate agreements provide a “more effective road map to peace.” Others argue that comprehensive peace agreements might come off as a laundry list of compromises, resulting in half-hearted implementation and the eventual return to violence. Additionally, third parties frequently become involved in civil wars through military interventions or by imposing sanctions on the conflict parties, adding another layer of complexity to the peace process and to the analysis of how best to create effective, long-lasting peace agreements.

By design, complex peace agreements address a wide range of issues, often including provisions for the reformation of many aspects of day-to-day life, including the military and police, the justice system, political institutions, and economic arrangements. These comprehensive agreements are assumed to be more effective at preventing a return to violence, as less ambiguity on key social and political issues would presumably make future conflict less likely. In this study, the authors discuss their original research on the causes and effectiveness of comprehensive agreements to seek answers to two main questions: 1) Are more elaborate and comprehensive peace agreements better able to keep the peace than less comprehensive agreements? And, 2) do third-party interventions impact the “elaborateness” of peace agreements and whether or not outstanding conflict issues remain unresolved?

To measure the complexity and the effectiveness of peace agreements, the authors used two datasets reflecting the design of 156 peace agreements signed between 1975 and 2011. With the first dataset, a peace agreement’s design was considered based on the number of provisions included. This number was then used to rank peace agreements by complexity (the more provisions included in the agreement, the more complex the agreement). Agreement effectiveness was determined by whether or not implementation failed within a year or armed conflict recurred within five years. The agreements were then analyzed in relation to a different dataset to measure the impact of third-party intervention on peace agreement design. Interventions were classified as either diplomatic (through mediation), economic (through sanctions), or armed. Armed interventions were classified by which side the third-party military supported—either the government or the rebelling forces.

The authors’ findings showed that agreements with a greater number of provisions (more complex) are less effective at keeping the peace, with violence more likely to return within five years. Also, outstanding issues left unresolved in the agreement do not necessarily result in the peace agreement’s failure. Regarding third-party intervention, the results showed that mediation or armed intervention in support of the government both correspond with more comprehensive peace agreements, whereas sanctions and armed intervention in support of rebel forces correspond with less comprehensive agreements. Additional control variables unrelated to the authors’ hypotheses were also examined, leading to a consistent finding that stronger rebel forces during civil war resulted in a lower likelihood of creating comprehensive agreements.

The authors suggest that these findings reinforce the notion that civil war resolution should be embraced as a process—and that this process takes time for trust to build within and between actors. Agreements with fewer provisions allow actors “the time necessary to convince their constituents and supporters to support resolution efforts and avoid being viewed as having sold out” by either abandoning their cause or failing to address issues important to their base. Agreements with fewer provisions also allow leaders to spend the necessary time addressing key issues, rather than spreading their time across many provisions that may not be as central to the conflict.

Contemporary Relevance

Of the more than 200 civil wars since the end of the Cold War, only 20% ended as a result of a military “victory,” while around one-third have ended in a ceasefire or peace agreement. Considering the prevalence of civil wars and the significant difference in success rates between peace agreements and prolonged military engagements, it is vital to continue the search for effective ways to improve agreement design and implementation. The internationalized civil wars in Syria and Yemen are two contemporary conflicts that have both been labeled the worst humanitarian crises of our time. In Syria, hundreds of thousands of people have been killed and millions are on the run and in need of humanitarian assistance. In Yemen, there is a risk of widespread famine and an existing cholera epidemic. Better understanding civil wars, how they end, and how they are less likely to recur cannot be any timelier.

Practical Implications

As this research shows, a signed peace agreement—even, and perhaps especially, one with long lists of provisions—does not guarantee peace. Civil wars end, yet research suggests they tend to recur. A key task will always be to better understand peace agreement design and how sustained peace can be achieved.

The authors of this article suggest that peace agreement design, peace process dynamics, and the experiences of conflict experts and practitioners need to inform meaningful advances in conflict resolution policies. A valuable contribution at the nexus of research and practice is the Peace Accord Matrix (PAM; https://peaceaccords.nd.edu). Members of the research team monitor ongoing peace processes on issues of design and implementation. This kind of assessment, according to the PAM project, “enables and facilitates early preventative action and the generation of options for potentially needed innovation in the process of implementation.”

The research findings here are important because of how they point to different conclusions than what is easily recognized. It is logical to assume that complex agreements designed with provisions addressing all aspects of the conflict would be superior to agreements with fewer provisions. This research can inform the practice of international mediators, whose expertise might lead them to work toward highly complex peace agreements. With thorough examination of the context (i.e., conflict analysis/conflict mapping), however, they might recognize that even in peace agreements for complex civil wars, as this research suggests, sometimes less is more.

Continued Reading

- Peace Accords Matrix By the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame. https://peaceaccords.nd.edu/

- Understanding Quality Peace Edited by Madhav Joshi and Peter Wallensteen. New York: Routledge, 2018.