This analysis summarizes and reflects on the following research: Mpofu-Walsh, Sizwe. (2022). Obedient rebellion: Conceiving the African nuclear weapon-free zone. International Affairs, 98(1), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab208

Talking Points:

- The African nuclear weapon-free zone—as a form of “obedient rebellion”—is central to challenging the global nuclear order.

- The African nuclear weapon-free zone conforms to the global nuclear order as a feature of international nuclear weapons law (a form of “obedience”).

- The African nuclear weapon-free zone rejects the global nuclear order by articulating the need to eliminate nuclear weapons and centering African agency so that complete decolonization can be advanced (a form of “rebellion”).

Key Insight for Informing Practice:

Stakeholders such as academics, practitioners, policy-makers, political leaders, funders, and activists must learn from the “obedient rebellions” of nuclear weapon-free zones and center Global South perspectives and choices when navigating the existential threats of nuclear weapons and peace and security issues more broadly.

Summary:

The global nuclear order, the process by which nuclear weapons affect the world order, is dominated by powerful states, mostly from the Global North, with excessive influence by nuclear weapons states (NWSs). The nuclear status quo is institutionalized in the United Nations. One need only look at the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (China, France, Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States) to recognize the importance of nuclear weapons in this global order. These five permanent members are recognized nuclear weapons states and tasked with maintaining international peace and security.1

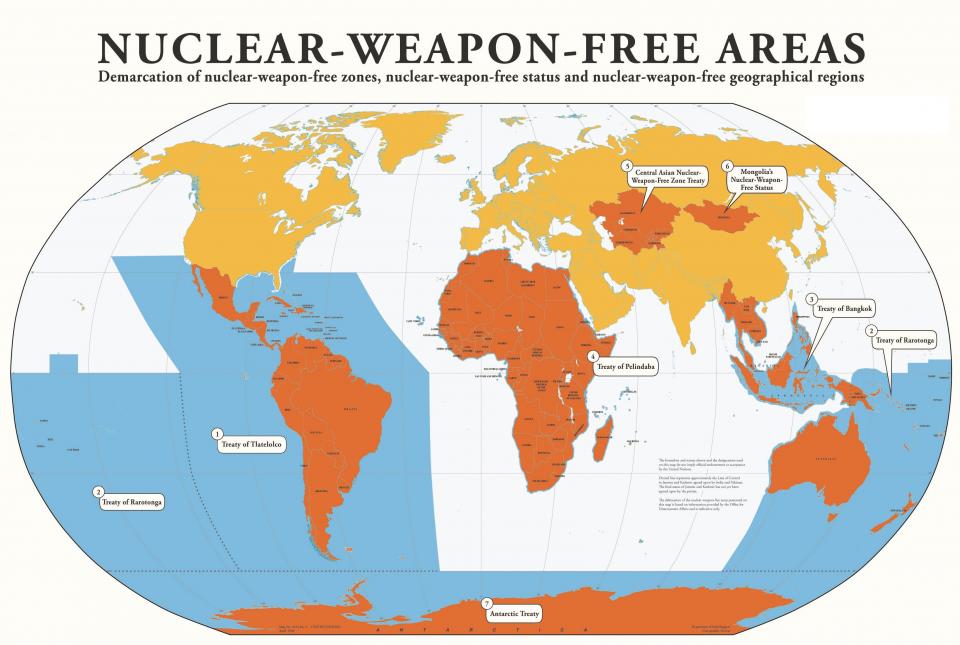

It is in this context that Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh examines Africa’s contributions to the nuclear order. The author argues that it is not only useful but essential to understand the African nuclear weapon-free zone (NWFZ) not as peripheral but as central to the nuclear order. Starting in the 1950s, NWFZs became a feature of the nuclear order, covering over 100 countries, the entire regions of Latin America, the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Central Asia (39 percent of the human population), and spanning the entire southern hemisphere. NWFZs “reveal the tensions inherent in nuclear order itself, through their locations in the Global South,” especially as many of those countries still grapple with legacies of colonialism. As Global South phenomena, NWFZs are largely rendered unimportant in a variety of theoretical perspectives by a so-called “great power gaze” (also: “white gaze”), which “systematically excludes evidence from African states as incidental.”

NWFZs operate in two distinct ways in the nuclear order. One the one hand, they link to Article VII of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which permits any group of states to establish a NWFZ with a legal prohibition on nuclear use. In that capacity, NWFZs conform to the global nuclear order as a feature of international nuclear weapons law. On the other hand, NWFZs reject the nuclear order by articulating the urgent need for the elimination of nuclear weapons and centering Global South agency so that complete decolonization can be advanced.

These contending approaches to the nuclear order are examined through the lens of “obedient rebellion” by African states. “Rebellion” centers around the association of nuclear weapons with colonialism and therefore the association of NWFZs with anti-colonial resistance. This link and the African attitude towards the nuclear order manifested themselves most clearly in response to the French nuclear tests in the Sahara between 1960 and 1966. Nuclear colonialism was challenged by African leaders in the 1960s through their rejection of nuclear defense and of NWSs’ military bases on the African continent, their critical attention to the borderless consequences of nuclear fallout and to the general disregard for African agency in decisions about nuclear testing, and their calls for complete disarmament.

At the same time, newly decolonized African states sought inclusion in global institutions. While decrying the inequality of the nuclear order, they therefore also enacted a form of “obedience” by accepting the legitimacy of that order and seeking recognition within it. African states have actively participated in the nuclear order, within the context of the United Nations, by attending global conferences such as the Bandung Conference of 1955, the 1961 Non-Aligned Movement’s summit in Belgrade, or the founding conference of the Organization of African Unity in 1963, as well as by joining nuclear institutions and accepting their rules by signing and ratifying global nuclear treaties (e.g., NPT, Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, or Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons). By doing so, they have thereby accepted the norms set out by these institutions, instead of boycotting them or pursuing nuclear weapons. The anti-colonial tone, the seeking of recognition, and the notion of respect for Africa have been prominent features throughout this history. In sum, the Africa NWFZ symbolizes “both postcolonial anti-nuclear solidarity and nuclear responsibility; it represent[s] both ‘obedience’ to and ‘rebellion’ against global nuclear order.”

| Bandung Conference, held in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955, was the first large-scale meeting of Asian and African countries, the aims of which were economic and cultural cooperation and opposition to (neo)colonialism. |

| Great power gaze focuses on ideas and theories from the Global North, and “systematically excludes evidence from African states as incidental.” |

| Non-Aligned Movement is a group of 120 countries that formed during the Cold War to resist alignment with either of the two emerging power blocs (associated with the U.S. and the Soviet Union). |

| Nuclear weapon-free zone (NWFZ): prevents the stationing, stockpiling, acquisition, retention, transport, and use of nuclear weapons in a given area. Currently NWFZs cover Africa, Antarctica, Latin America and the Caribbean, the South Pacific, South East Asia, Central Asia, the sea bed, outer space, and the moon. |

Informing Practice

The community working to reduce the threat of nuclear weapons and toward their total elimination must not dismiss nuclear weapon-free zones (NWFZs) as sideshows of the great power struggles over nuclear weapons. Through this article we have learned about the agency of African states choosing and actively pursuing a different path than that charted by the powerful nuclear weapons states. African states created a way to conform to parts of the nuclear order while at the same time challenging not only the nuclear but also the global order.

This article makes a powerful case that “African agency matters to international outcomes.” The author aptly challenges the field of International Relations to reject the idea that “events in the North map onto the South.” Indeed, disrupting this “great power gaze” in academia must be part of broader efforts by multiple stakeholders—such as academics, practitioners, policy-makers, political leaders, funders, and activists—to reject the idea that only major states and its elite actors get to define and comment on the structure of international politics

NWFZs have played an important role in the nuclear order and are shaped by Global South countries’ agency and considerations that go beyond non-nuclear commitments in the NPT. NWFZs are situated in the realm of nuclear security but reach into areas of governance, regional collaboration, trustbuilding, the environment, non-nuclear security arrangements, and peace and security issues more broadly—all areas that are relevant in the contemporary context of United Nations conferences aimed at establishing a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and all other Weapons of Mass Destruction. If those of us who recognize the existential threat of nuclear weapons and advocate for complete nuclear disarmament seek effective tools for strengthening the global norm of prohibition, we must learn from NWFZs. One particularly useful insight gained from NWFZs is the link between decolonization and denuclearization. Building on this link, nuclear abolition activists can aim to dismantle the racism-militarism paradigm upholding the global nuclear order, which is based upon “a largely unacknowledged doctrine of white supremacy and the necessity of violence to uphold it.”2

African perspectives must be centered—and not reduced to signature issues such as underdevelopment, development, race, resource exploitation, and internal conflicts—in efforts to repudiate the racism-militarism paradigm and build a world that is based on equality, rights, dignity, justice, peace, shared wealth, and sustainability. The renowned economist and peace advocate Kenneth Boulding reminded us that “what exists is possible.” NWFZs exist; they are not a sideshow to great power politics. It is our collective obligation to broaden our efforts to diversify voices and perspectives and learn from the “obedient rebellions” of NWFZs, centering Global South perspectives and choices while navigating the existential threats of nuclear weapons and peace and security issues more broadly. [PH]

Footnotes:

1. For a comprehensive book on the global nuclear order see: Kutchesfahani, S. Z. (2018). Global Nuclear Order. Routledge.

2. Booker, S., & Ohlbaum, D. (2021). Dismantling racism and militarism in U.S. foreign policy. A discussion paper. Center for International Policy and FCNL Education Fund. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.fcnl.org/dismantling-racism-and-militarism-us-foreign-policy

Questions Raised: What are ways that Global North stakeholders or those from traditionally dominant groups seeking to disrupt the “great power gaze” can support the centering of African perspectives on peace and security issues?

Continued Reading:

Bosman, I. (N.d.). Nuclear disarmament: What the world can learn from Africa. South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA). Retrieved April 4, 2023, from https://saiia.org.za/research/nuclear-disarmament-what-the-world-can-learn-from-africa/

Collin, J.-M., & Cooper, A. R. (2021, June 3). Africa and the atomic bomb: Part II. Inkstick. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://inkstickmedia.com/africa-and-the-atomic-bomb-part-ii/

Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. (2023, March 14). Fact-sheet: Nuclear-weapon-free zones. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://armscontrolcenter.org/nuclear-weapon-free-zones/

Haastrup, T., & Möser, R. (2021, June 9). Africa and the atomic bomb: Part III. Inkstick. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://inkstickmedia.com/africa-and-the-atomic-bomb-part-iii/

International Development Working Group. (2022). Decolonizing international development. Women of Color Advancing Peace & Security. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://issuu.com/wcapsnet/docs/idwg_policy_paper.final_copy

Love, A. (2022). Recognizing, understanding, and defining systemic and individual white supremacy. Women of Color Advancing Peace and Security. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://issuu.com/wcapsnet/docs/recognizing_understanding_and_eradicating_system

Nuclear Threat Initiative. (n.d.) Pelindaba Treaty. African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (ANWFZ) Treaty. Retrieved, April 5, 2023, from https://www.nti.org/education-center/treaties-and-regimes/african-nuclear-weapon-free-zone-anwfz-treaty-pelindaba-treaty/

Samuel, O., & Pretorius, J. (2021, May 26). Africa and the Atomic Bomb: Part I. Inkstick. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://inkstickmedia.com/africa-and-the-atomic-bomb-part-i/

Organizations:

African Commission on Nuclear Energy (Pelindaba Treaty): https://www.afcone.org

Women of Color Advancing Peace and Security: https://www.wcaps.org/

Keywords: Africa, decolonization, disarmament, nuclear-weapon-free zones

Photo credit: U.N. Photo