This analysis summarizes and reflects on the following research: Åse, C., & Wendt, M. (2021). Gendering the military past: Understanding heritage and security from a feminist perspective. Cooperation and Conflict, 56(3), 286-308. DOI: 10.1177/00108367211007871

Talking Points

In the context of two military heritage sites in Sweden:

- Gender and sexuality norms are employed at military heritage sites to reinforce traditional national security thinking on the necessity of protecting territory through military force.

- Military heritage sites use gender and sexuality—particularly ideas about the “’natural’ difference” between women and men—to evoke gendered security roles.

- Gender and sexuality are incorporated at military heritage sites to promote “nativist… conceptualizations of community,” through a visual/spatial merging of the national community with the (heterosexual) reproductive family.

Key Insight for Informing Practice

- Social movements can re-frame and transform gendered national security narratives towards more progressive, anti-war goals by first being mindful of how gender is used and the emotional response it elicits.

Summary

How does “the preservation of memories of geopolitical threats, conflicts, and military violence” influence national security politics? Also, how do these memories reinforce the gender binary and heterosexuality? Cecilia Åse and Maria Wendt analyze how military heritage sites “dis/encourage particular understandings of security and limit the range of acceptable national protection policies.” They find that gender and sexuality are used at military heritage sites to reinforce traditional national security thinking on the necessity of protecting territory through military force. This thinking is based on “the ‘naturalness’ of the gender binary and heterosexuality” wherein a male protector is necessary to defend the “feminine” home front. They examine military heritage through a feminist lens by visiting two military heritage sites in Sweden commemorating the Cold War—a period of remarkable domestic militarization due to the country’s position of “armed neutrality.”

This research combines gender analysis with critical heritage studies, specifically on military heritage, to “unpack[] the material, affective and embodied underpinnings of security understandings.” The emotional response that military heritage sites evoke is “political work,” meaning that the emotional response positions the individual in relation to a larger community, as well as in relation to implicit gendered and hierarchical understandings. Thus, visitors to military heritage sites are encouraged to feel certain emotions and to “feel threat, security or affinity to a (national) community.” The two military heritage sites at the center of this analysis preserve the history of Sweden’s military build-up during the Cold War: two exhibits at the Air Force Museum in Linköping (“If War Comes—Sweden during the Cold War”1 and “Secret Acts—The DC-3 that Disappeared”2) and the re-development of Bungenäs in northern Gotland, the location of a former Cold War military compound. Åse and Wendt visited these sites with a transdisciplinary research team, taking notes and photos of “the architectural and spatial arrangements of the sites” and their reactions.

With this context in mind, Åse and Wendt organize their findings on gendered national security and Cold War heritage in terms of territory, community, and body. With regards to territory, their analysis reveals how the military heritage sites use gender and sexuality to promote the idea of “national territory as needing protection,” particularly through reproducing ideas about the “’natural’ difference” between women and men and drawing on these to evoke gendered security roles. For instance, the exhibits at the Air Force Museum instill “a gendered protector-protected dynamic” through the installation of family homes below military planes. This “spatial arrangement” points to gendered obligations for the protection of the nation-state wherein men are expected to use violence (represented by the suspended military planes) and women are expected “to produce and care for the nation’s future citizens” (represented by the family homes). In Bungenäs, the re-development of the former military compound maintains a strong visual adherence to military design with strict rules against design elements associated with civilian or family life.

With regards to community, the authors reveal how gender is incorporated at the “heritage sites to confirm nativist and nationalist conceptualizations of community.” At the Air Force Museum, visitors first enter through the display of homes before viewing military equipment, thereby urged to “merg[e] familial history/genealogy with national history/genealogy.” The homes on display are representative of the “homeland” and emphasize heterosexuality through their representation of the “national community as the reproductive family.” The redevelopment of Bungenäs appeals to nationalist sentiments about Sweden’s armed neutrality during the Cold War—as a “neutral warrior” capable of and ready for defensive violence. By maintaining much of the military aesthetic of the original compound and banning a “homely aesthetic,” Bungenäs leans into its identity as masculine “protector” of the homeland, given its location on the Baltic Sea facing the former Eastern Bloc.

With regards to the body, the authors demonstrate how a feminist analysis of heritage sites reveals how gender is part of the physical experience of visiting these sites. For instance, at Bungenäs, visitors have a “bodily experience of crossing a civilian/military line” and embrace “the vantage point of an embodied soldier” through the architecture and layout of the site. Similarly, at the Air Force Museum, visitors are positioned as members of a heterosexual, Swedish nuclear family, shaping their understanding of the objects and messages in the exhibit.

Taken together, a feminist analysis of military heritage reveals how gender and sexuality are used to convey key national security narratives and priorities. Norms around gender and sexuality—namely, the dominance of the gender binary and heterosexuality—are deeply embedded in collective understandings of national security politics and thereby restrict what are deemed acceptable security policies.

Informing Practice

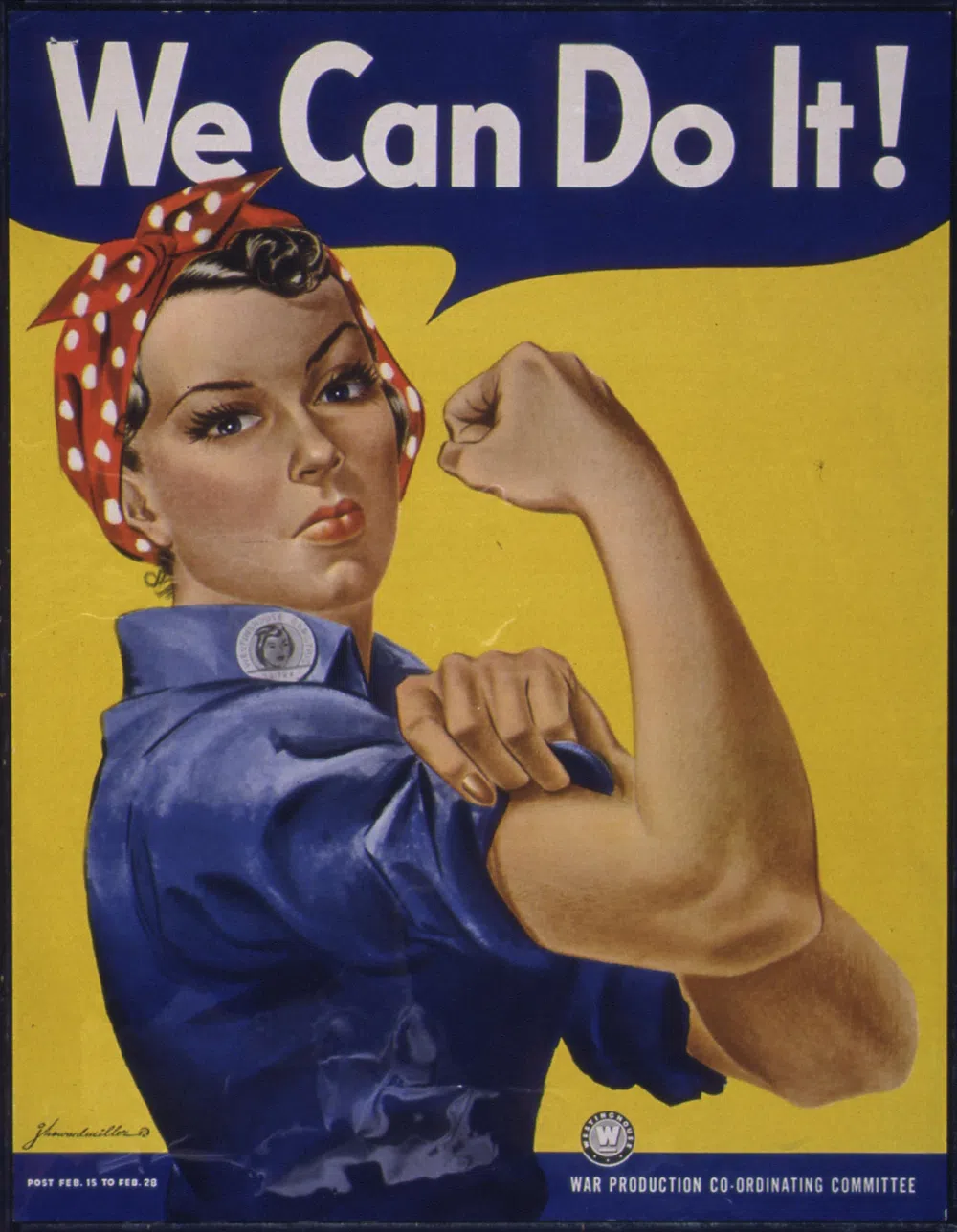

To the American public, Rosie the Riveter is an iconic poster from the WWII period depicting a white woman proudly showing off her arm muscles in the rolled-up sleeves of a work uniform, with the words “We Can Do It!” prominent in the background. The larger context of this poster points to the 1940s when women were (temporarily) encouraged to work in the defense industry producing a range of munitions and war supplies to support men fighting in WWII. Today, it is seen as an image of female empowerment having been co-opted by feminist movements as a sign of gender equality—that women can do anything that men can do. The transformation of the collective understanding of this image, from supporting the war effort to gender equality, demonstrates the ability of social movements to change the meaning of national security images. Is it possible for social movements to go further and re-frame and transform gendered national security narratives in the pursuit of anti-war goals?

Images like Rosie the Riveter rely on our collective memories as Americans to convey meaning, particularly evoking a nationalist and patriotic emotional response. While most Americans today were not alive to remember the experience of WWII, many grew up listening to the stories of their parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents about their personal experiences or watching the numerous and critically acclaimed movies or TV shows recounting WWII stories. These stories often stress the value of personal sacrifice, putting one’s country before oneself, and (more to the point) the necessity of military force to defend freedom and democracy around the world.

| Collective memories: | Coined by French philosopher Maurice Halbwachs, meaning, “the memories of a group generated through shared experience and values.” |

The military heritage preserved in these stories implicitly justifies how the U.S. defense industry and military have grown in the decades since WWII, suggesting that all the wars and military interventions since then have been necessary to defend our collective values of freedom and democracy. Yet, the reality of U.S. warfare is far removed from these idealistic visions. For instance, The Costs of War Project at Brown University outlines the realities of the U.S.’s post-9/11 wars, detailing countless casualties and human rights and civil liberty violations in the U.S and abroad, counterterror activities in 85 countries, and over $8 trillion spent on warfare that ultimately failed at its stated goals.

With this in mind, how can this research by Åse and Wendt inform anti-war movements? One critical take-away is to be mindful of how gender is employed to advance national security narratives and ultimately limit the range of conceivable policy options. Gender is a contested space with no single definition or collective understanding of its meaning. This provides opportunities to seize on gendered imagery and messages in national security dialogue currently used in support of war-making and re-frame and transform them in the service of war resistance. Additionally, it is important to record the emotional response elicited by national security images and messages. This allows for a deeper analysis of the cultural attitudes, values, and systems that are reinforced in these messages and creates a starting point for social movements to align their own anti-war messaging. [KC]

Questions Raised

How can social movements re-frame and transform gendered national security narratives in the pursuit of more progressive and perhaps even anti-war goals?

Continued Reading

Shaz, S. (2023, May 30). From the Cuban Missile Crisis to Russia’s War in Ukraine: Strategic empathy as feminist foreign policy. Peace Science Digest. Retrieved on August 2, 2023, from https://warpreventioninitiative.org/peace-science-digest/from-the-cuban-missile-crisis-to-russias-war-in-ukraine-strategic-empathy-as-feminist-foreign-policy/

Peace Science Digest. (2023, May 3). Facts change Americans’ beliefs about the actual risks of terrorism. Retrieved on August 2, 2023, from https://warpreventioninitiative.org/peace-science-digest/facts-change-americans-beliefs-about-the-actual-risks-of-terrorism/

Roediger, H. L. III, & DeSoto, K. A. (2016, June 28). The power of collective memory. Scientific American. Retrieved on August 3, 2023, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-power-of-collective-memory/

Zaromb, F., et al. (2014). Collective memories of three wars in United States history in younger and older adults. Memory & Cognition, 42, 383-399. https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13421-013-0369-7

Organizations

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum: https://www.cooperhewitt.org/channel/designing-peace/

The Costs of War Project: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/

Photo credit: Rawpixel