Following the presidential elections in November 2024, the second Trump administration moved swiftly to embed its MAGA agenda into the core operations of the U.S. government. The vicious targeting of immigrants without concern for constitutionally protected rights to due process, assaults on the freedom of press, attacks on the courts and judges, and the total dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) without Congressional approval and hostile take-over of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) by DOGE are prime examples of an entirely new era for American politics. Analysts most accurately describe this new context as competitive authoritarianism, where a democratically elected leader erodes the system of checks and balances, surrounds themselves with loyalists in key positions, and attacks independent actors such as the media, universities, and nongovernmental organizations.

The articles selected for May 2025’s Peace Science Digest focus on authoritarianism: the varied ways in which authoritarianism affects society and how people can rise together to defend democracy through nonviolent means. This round-up is not comprehensive or reflective of all the academic scholarship on authoritarianism, but rather offers a few recent scholarly contributions to understanding and contextualizing the current trend towards authoritarianism in the United States and around the world.

First, we draw out the main findings from five recent journal articles discussing these themes from different perspectives and in different contexts. Then, in the Informing Practice section, we reflect on some common themes—namely, how narratives and information politics shape public support for democracy or authoritarianism, suggesting a critical need for pro-democracy, pro-human rights, and pro-peace coalitions to actively pursue narrative strategies that can build momentum against and withstand rising authoritarianism.

Article Summaries

A Post-Truth World: The Struggle over Definitions and Narratives

The following bullet points summarize research from: Bowsher, J. (2024). After truth, after shame … after information politics? Rethinking the epistemologies of human rights in the digital-authoritarian conjuncture. The International Journal of Human Rights, 28(8–9), 1501–1525. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2024.2315277

How can human rights organizations adapt their approach to advocacy in an era of heavy disinformation and eroding trust in facts?

- Human rights advocacy groups have traditionally relied on “information politics” (brute, “objective” truths and facts) as a means of influencing (through “shaming”) the behavior of governments/states that are impeding the rights of people within and beyond their borders, but these shame-based approaches are losing their effectiveness.

- The current digital age—where information is determined through algorithms and content manipulation—creates ripe conditions for authoritarian regimes to run disinformation campaigns to control narratives, contest facts, or outright ignore ones that do not suit their agenda.

- Human rights groups and justice advocates must rethink how knowledge is produced and used, while also becoming more politically and culturally embedded (moving away from the myth of “neutrality”), more confrontational in the face of power, and further engaged with the public in the struggle over meaning.

Nationalism and Violence against Marginalized Groups

The following bullet points summarize research from: Rains, M., & Hill, D. W. (2024). Nationalism and torture. Journal of Peace Research, 61(5), 794-807. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234332311644

Why do governments—particularly democratic governments—engage in non-repressive violence against marginalized groups?

- Exploring why non-repressive state violence happens almost as frequently in democracies as it does in autocracies, the authors hypothesize that such violence against marginalized groups in particular will happen in democracies “more frequently when nationalist parties are in control of the government,” as a nationalist leader’s political base will be less opposed to—or may actually support—violence against those seen as outside the “national” identity group and therefore as threats to public safety.

- Drawing on statistical analysis of torture (as one form of violence) in democracies and autocracies led by different ideologies, the authors find that “democratic, nationalist-leaning governments are more likely to torture marginalized groups and criminal suspects than democratic governments” with other ideological leanings.

- The same relationship between a nationalist government and torture against marginalized groups does not hold in autocratic countries, suggesting that the mechanism has something to do with “government responsiveness to the public’s preferences” in democracies.

- A nationalist government sets the stage for such violence by dehumanizing marginalized groups, which makes members of the dominant group less concerned about harm against them, and by “dismantling institutions that protect marginalized populations from oppression” and weakening enforcement mechanisms against abuse by undermining the credibility of or ignoring the judiciary.

- The mere “presence of institutions meant to hold agents accountable does not guarantee lower levels of state violence” as nationalist governments can ignore or “actively undermine institutions meant to protect groups who do not make up their intended political base,” especially if members of this base do not “care about the abuse of marginalized people.” What matters is not so much the existence of these institutions but the relationship of the public and the government to these institutions.

Following Orders or Following the Oath in the U.S. Military Officer Pipeline

The following bullet points summarize research from: Brooks, R. A., Robinson, M. A., & Urben, H. A. (2023). Following orders or following the oath? Assessing democratic norm endorsement among service academy cadets. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 68(7-8), 1279-1306. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027231195385

How strongly do future U.S. military officers believe in democratic values, like supporting the Constitution and the ethics of not taking partisan sides?

- The researchers investigate whether service academy cadets internalize the military’s professional standards, particularly the duty to uphold democratic values, even when they conflict with partisan loyalties or orders from civilian leaders.

- The study shows that service school cadets have a pattern of “selective endorsement” of democratic norms. This means that they support these norms in theory, but they often give up on them when they go against their partisan beliefs. An experiment showed a big difference between how cadets felt in public and how they felt in private. For example, 73% of cadets stated in public that they would refuse anti-democratic orders, but only 40% expressed the same sentiment in private.

- In their professional journey, cadets valued technical knowledge more than avoiding political bias, which suggests that the value of avoiding political bias is not deeply ingrained. Additionally, cadets from districts that lean toward Trump were significantly less likely to support defying anti-democratic orders, highlighting the importance of partisan context.

- This “selective endorsement” suggests that socialization into military professionalism is not complete and that political identity can take precedence over constitutional duties, which is problematic for the relationship between the military and the civilian government in a democracy.

Fostering Democratic Participation under Autocratic Rule

The following bullet points summarize research from: Ong, E., & Rahmad, S. B. (2023). Civil society collective action under authoritarianism: Divergent collaborative equilibriums for political reform in Malaysia and Singapore. Democratization, 31(3), 551–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2023.2223142

Under what conditions do civil society organizations (CSOs) in authoritarian regimes engage in collective action for political reform?

- Civil society organizations (CSOs) function differently based on their local contexts, even when under similar forms of autocratic governance, as in Malaysia and Singapore (both considered to be electoral autocracies).

- In Malaysia, where public interest and support for political reform is high, CSO leaders feel motivated (psychologically) and supported (financially, not reliant on state-funding) by the public, thus motivating CSO leaders to collaborate with other CSOs in “high profile activities,” thereby increasing mutual trust and confidence while raising public awareness on the importance of civil society’s democratic participation—creating a positive feedback loop.

- In Singapore, where there is higher trust in government and less concern about electoral integrity, there is low public interest in political reform, which results in Singapore’s CSO leaders feeling less motivated and more fragmented—focusing on niche policy areas—and exhibiting greater fear of governmental repression.

- A more autocratic but well-managed regime may emerge as more popular with the public: How Singapore’s administration navigated through the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 created a positive association between the people and the State, due to strategic governmental policies that reduced the financial strain on its people during that period. In Malaysia, the same crisis created the conditions for greater political consciousness and desire for reform due to fragmentation and disdain between people and the government.

Transnational Networks Critical to Supporting Local Pro-Democracy Coalitions in Authoritarian Contexts

The following bullet points summarize research from: Casarões, G., do Monte, D. S., & de Carvalho Hernandez, M. (2024). Safeguarding democracy from the outside in: Transnational democratic networks against autocratisation in contemporary Brazil. Third World Quarterly, 46(2), 215–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2024.2360537

How did Brazil successfully resist emerging authoritarianism?

- This article traces threats to Brazilian democracy from the 2016 impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff to the 2022 Presidential elections that saw incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro lose to President Lula da Silva.

- Support from transnational networks to the opposition party and Brazilian civil society organizations was an important factor in preventing the far-right government of President Jair Bolsonaro from staging a coup following the 2022 presidential elections.

- Domestic groups use transnational networks to support democracy through the following strategies:

- Persuasion, which “aims to change the government’s preferences through material and/or normative arguments,” and

- Public pressure, which “seeks to raise social opposition and change public opinion by mobilizing international non-governmental organizations, foreign governments and international organizations in naming and shaming strategies.”

- The relationship between domestic groups and transnational networks shifts the cost-benefit analysis of the government by “increas[ing] the cost of the political decision by engaging with international actors who can impose political, economic, or ideational constraints [like] the suspension or termination of diplomatic relations, restrictions on trade, or even military and economic sanctions.”

- Transnational networks are cross-border associations “among sub-national actors to collaborate or form new relationships for shared economic, political, cultural, and social agendas,” without the involvement of governments.1 For example, this paper draws out how a transnational network of local and global environmental organizations, scientists and academic communities, Indigenous groups, and lawyers documented increasing deforestation rates in the Amazon under President Jair Bolsonaro. Indigenous nations targeted by deforestation, in partnership with international environmental non-profits and lawyers from the U.S., France, and Brazil, sued President Bolsonaro for genocide and ecocide at the International Criminal Court.

Informing Practice

Resisting authoritarianism requires an active civil society to engage in nonviolent efforts to defend democracy. The analyses reviewed above identify key threats to democracy and opportunities to protect it. An over-arching theme connecting these articles is how narratives and information politics shape public support for democracy or authoritarianism—suggesting a critical need for pro-democracy, pro-human rights, and pro-peace coalitions to actively pursue narrative strategies that can build momentum against and withstand rising authoritarianism.

- Bowsher (2024) spells out how new information politics in the digital-social media age allow autocrats to dispel truth in favor of their own propaganda, underscoring the need for human rights and justice groups to reject “neutrality” in their pro-democracy messages.

- Rains & Hill (2024) identify how nationalist governments employ the politics of dehumanization in relation to nationalist public safety discourses to shape and respond to voters’ support for targeted violence against minority groups.

- Brooks, Robinson, & Urben (2023) reveal a critical vulnerability in the U.S. military’s officer pipeline: many future officers endorse democratic norms only when those norms do not conflict with their partisan beliefs. . This points towards a corrosive effect of political polarization and anti-democratic narratives on institutions mandated to uphold democracy.

- Ong & Rahmad (2023) explore how public support for civil society organizations is conditioned by how well governments—whether democratic or autocratic—respond to crises.

- Casarões, do Monte, & de Carvalho Hernandez (2024) show how pro-democracy coalitions can leverage local and transnational networks for narrative success, resulting in positive political outcomes, like preventing a coup.

Our task now is to reflect on how this recent research might apply to the threat of authoritarianism in the United States and where pro-democracy narratives can best be leveraged. In a deeply militarized context like the U.S., where warfare and violence are heralded as the means to protect freedoms and collective security, the country is at a particularly dangerous moment—especially to the extent that some might endorse the misguided belief that armed resistance is the only way to counter authoritarianism.

One authoritarian tactic is to instill doubt and fear among the public and to repress the right to free speech and assembly. Narratives that dehumanize or “otherize” specific groups work to justify violence or other extraordinary measures against them, as we have seen against students peacefully organizing for Palestinian lives on college campuses like Mahmoud Khalil, Rumeysa Ozturk, and Mohsen Mahdawi. These students have been met with state-sanctioned violence, detainment, and attempted deportation. And yet, they have remained steadfast in using nonviolent resistance to demand that universities divest from arms manufacturers and that the U.S. government stop enabling the genocide of Palestinians, including under the Biden administration.

Are these students “pro-terrorist” leaders or peace and justice advocates? Bowsher’s work informs us of the importance of struggling over meaning and being politically embedded rather than embodying positions of faux neutrality. Who gets to determine the narratives that give shape to these contrasting labels? Which narratives do we propagate in our own lives, whether in discussions at work or in social spaces? The repression of the civil liberties of a few can easily cascade into repression for many, and eventually the majority. This mass repression happens when autocratic regimes feel emboldened by a lack of pushback or even by “preemptive compliance” from institutions and corporations seeking to maintain their position(s) of privilege by siding with the authoritarian regime.

Authoritarians also seek to diminish pillars of a free society that would otherwise restrain their power, like the courts, the media, or civil society. We are witness to direct attacks against all of the above, for instance: the FBI’s arrest of Wisconsin Judge Hannah Dugan, the White House revoking media access to the Associated Press, and (of late) the inclusion of “Non-Profit Killer Bill” language in the House budget proposal. It is exhausting to witness the endless incursions against democratic norms and values—and that generates confusion and uncertainty about how to respond. Here, cross-sector collaboration and solidarity are critical to protect democracy. Ong & Rahmad’s piece calls on civil society to collaborate broadly and to be more robustly involved in voicing dissent against harmful authoritarian rhetoric and policies.

A good example of this sort of broad-based collaborative resistance are the anti-Trump and anti-MAGA rallies that have erupted across the U.S., some of which were organized by 50501—a strictly nonviolent grassroots organization that consists of everyday Americans, from veterans to civil servants—in collaboration with other peace and justice organizations such as NoVoiceUnheard and Build The Resistance. In consideration of Brooks and Robinson’s findings—that partisan allegiance of active military personnel may take precedence over constitutional obligation, which can be a dangerous dynamic in any democracy—any attempt to bridge the civil-military divide and/or the partisan divide and to foster mutual understanding and trust is a worthwhile endeavor. Thus, cross-cutting protests such as ones organized by 50501 are important for building bridges between different segments of society, as well as for advancing narratives that support democracy, peace, and human rights.

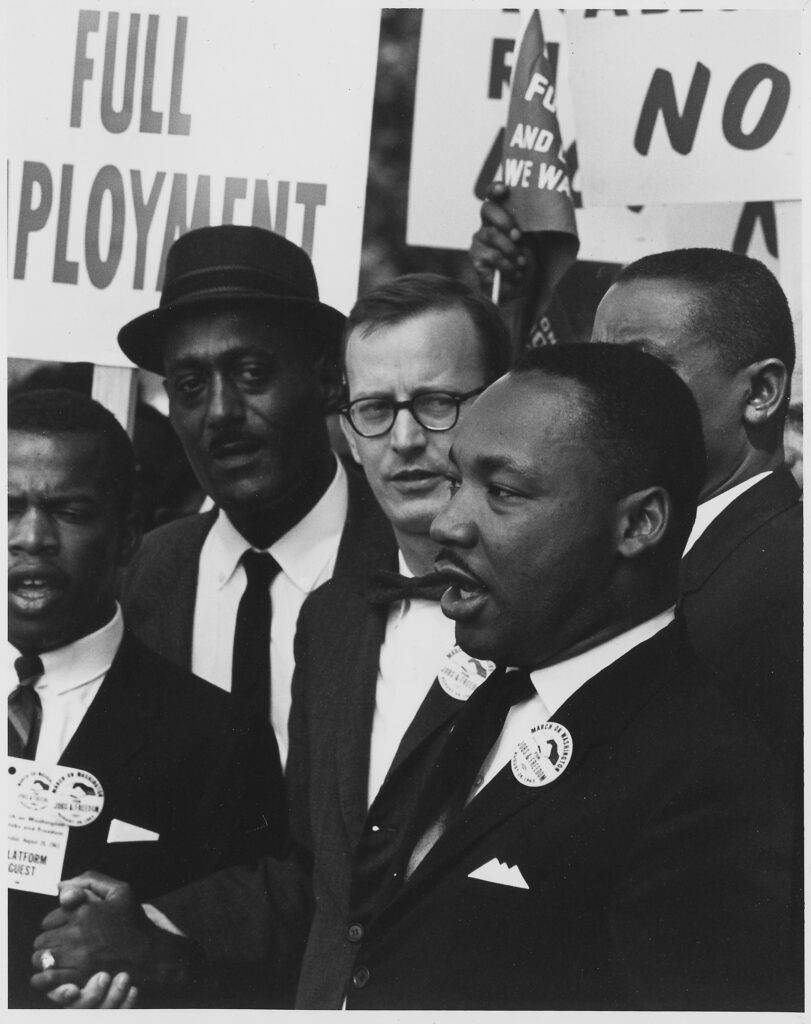

Casarões et al.’s research reminds us that power ultimately comes from the people and that collaborative nonviolent resistance between networks of people, both domestically and transnationally, can be leveraged to defend democracy—by asserting public pressure through protests and shaming or by making anti-democratic maneuvers more expensive or difficult. We can state with full confidence: nonviolence is not passivity. Rather, it is a form of strategic and ethical resistance that values human life and dignity in pursuit of justice and freedom. Historically, principled nonviolent campaigns have been the most effective tool against authoritarianism. In the U.S., we can look to our own history of nonviolent struggle that has successfully created a more democratic country, despite the militarized norms that might lead us to believe that violence is necessary to ensure freedom. Black Americans overturned Jim Crow laws and saw the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts achieved through strategic and principled nonviolence. Cesar Chavez successfully campaigned for farm workers’ rights by employing nonviolent tactics and the civil rights rhetoric of the 1960s. Looking further back in the historical record, women achieved the right to vote through sustained nonviolence and civil disobedience, embodied in the actions of trail-blazing suffragists like Alice Paul.

These examples call on us to take pride in the many ways that our country has become more free and more equal as the result of nonviolent action for peace and democracy—and they also remind us that there is a more strategic way to counter and defeat authoritarianism than armed resistance. Nonviolent resistance against authoritarianism demands discipline, courage, and collective effort, but in the words of Mohsen Mahdawi upon his release from unlawful ICE detention: “The people united will never be defeated. Justice is inevitable.”

Continued Reading

Continued Reading on Resisting Authoritarianism

- The claim that “no government has withstood 3.5%” of their population mobilizing for change is investigated here: Chenoweth, E. (2020). Questions, answers, and some cautionary updates regarding the 3.5% rule. Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/carr/publications/questions-answers-and-some-cautionary-updates-regarding-35-rule

- Read this book on how democracies can backslide into autocratic rule under certain conditions: Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How democracies die. Crown Publishing Group.

- Study the pillars of support that states and governments rely upon to maintain power: Popovic, S., Djinovic, S., Milivojevic, A., Merriman, H., & Marovic, I. (2007). Pillars of support. In CANVAS core curriculum: A guide to effective nonviolent struggle. Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Pillars-of-Support-PDF-English.pdf

- Read this book on how to resist authoritarian rule: Snyder, T. (2017). On tyranny: Twenty lessons from the twentieth century. Tim Duggan Books.

Continued Reading on Navigating the Post-Truth World

- The articles below explore how human rights activists and those in the humanities can adapt their strategies to the current era of disinformation, populism, and eroding trust in facts:

- Brown, S. (2018, April 2). Human rights in a post-truth era: What kind of activism? OpenGlobalRights. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://www.openglobalrights.org/human-rights-post-truth-era-activism/

- Zamora, L. (2023, March 13). The humanities as a compass: Navigating a post-truth era. JSTOR Daily. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://about.jstor.org/blog/the-humanities-as-a-compass-navigating-a-post-truth-era/

Continued Reading on Nationalism and Violence

- Examine this paper that looks at the relationship between Christian nationalism in the United States, and attacks against religious minorities in the country: Saiya, N., & Manchanda, S. (2024). Christian Nationalism and violence against religious minorities in the United States: A quantitative analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 64(1), 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12942

- View the key characteristics of white nationalist ideology, here: Facing History & Ourselves. (2019, August 9). White nationalism. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/white-nationalism

- Understand the impacts of nationalism and its ideologies here: CFR Education. (2023, February 16). Understanding the constructive and destructive natures of nationalism. Retrieved May 19, 2025, from https://education.cfr.org/learn/reading/understanding-constructive-and-destructive-natures-nationalism

- View this piece exploring how the concept of the nation-state is synonymous with genocide: Wade, F., & Mamdani, M. (2024, January 9). The idea of the nation-state is synonymous with genocide: An interview with Mahmood Mamdani. The Nation. Retrieved May 19, 2025, from https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/mahmood-mamdani-nation-state-interview/

- Read this news article observing the nationalist forms of violence between India and Pakistan: Jagarnath, V. (2025, May 12). India, Pakistan and the theatre of nationalist violence. Mail & Guardian. Retrieved May 19, 2025, from https://mg.co.za/thought-leader/2025-05-12-india-pakistan-and-the-theatre-of-nationalist-violence/

- Read this executive summary exploring Chrisitan nationalism in all 50 states across the U.S.: PRRI. (2025, February 4). Christian nationalism across all 50 states: Insights from PRRI’s 2024 American values atlas. Retrieved May 19, 2025, from https://www.prri.org/research/christian-nationalism-across-all-50-states-insights-from-prris-2024-american-values-atlas/

- Study this paper on police brutality in the U.S from 1980-2019: GBD 2019 Police Violence US Subnational Collaboration. (2021). Fatal police violence by race and state in the USA, 1980–2019: A network meta-regression. The Lancet, 398(10307), 1239-1255. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)01609-3/fulltext

Continued Reading on Democracy in Malaysia and Singapore

- This opinion piece highlights how political diversity and the seeking of accountability by young voters in Singapore reflects a flourishing democracy: Bloomberg Opinion. (2025, April 30). Singapore’s election shows its democracy is growing up. Bloomberg. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2025-04-30/singapore-s-election-shows-its-democracy-is-growing-up

- This article shines light on the history of the Bersih movement in Malaysia: Khoo, Y. H. (2021, October 6). The Bersih movement and democratization in Malaysia. International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/blog_post/the-bersih-movement-and-democratization-in-malaysia/

- This historical document by the Office of Foreign Relations of the United States records the context of the split between Malaysia and Singapore in 1965: U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXVI, Indonesia; Malaysia-Singapore; Philippines, Document 270. Office of the Historian. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v26/d270

Continued Reading on Democracy in Brazil

- This text uncovers how former president, Jair Bolsonaro, attempted to steal Brazil’s 2022 election: De Bruin, E. & Sullivan, H. (2025, January 8). How Jair Bolsonaro plotted to steal Brazil’s 2022 election. Good Authority. Retrieved May 1, 2025, from https://goodauthority.org/news/brazil-coup-plot-jair-bolsonaro-steal-election-2022/

- This paper explores the situation in Brazil after the Lava Jato scandal: Varley, P. (2024, October 3). Milestone or misstep? Corruption, development, and democracy after Brazil’s Lava Jato Probe. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://case.hks.harvard.edu/milestone-or-misstep-corruption-development-and-democracy-after-brazils-lava-jato-probe/

- This article highlights ways the people of Brazil can prevent an authoritarian resurgence: Bradlow, B. H. & Kadivar, M. A. (2023, January 12). How Brazil can prevent an authoritarian resurgence: A robust civil society can stop the far right. Foreign Affairs. Retrieved May 2, 2025, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/brazil/how-brazil-can-prevent-authoritarian-resurgence

- This video looks at President Lula da Silva’s career and how his second presidency will be different from the last: Elidrissi, R. & Ellis, S. (2022, October 25). Brazil’s likely next president, explained. Vox. Retrieved May 1, 2025, from https://www.vox.com/videos/2022/10/25/23422828/brazil-lula-bolsanaro-presidential-election

Continued Reading on Continued Reading on the Role of the Military in Upholding the Constitution

- This article urges renewed attention to the military’s apolitical role: Rasmussen, P. (2024, September 4). The anonymous military leaders with the weight of the election on their shoulders. Just Security. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://www.justsecurity.org/99802/military-leaders-democracy/

- A bipartisan group of former defense leaders reaffirms civilian control of the military and urges strict adherence to constitutional norms to safeguard democracy in this open letter: War on the Rocks. (2022, September 6). To support and defend: Principles of civilian control and best practices of civil-military relations. Retrieved May 21, 2025, from https://warontherocks.com/2022/09/to-support-and-defend-principles-of-civilian-control-and-best-practices-of-civil-military-relations/