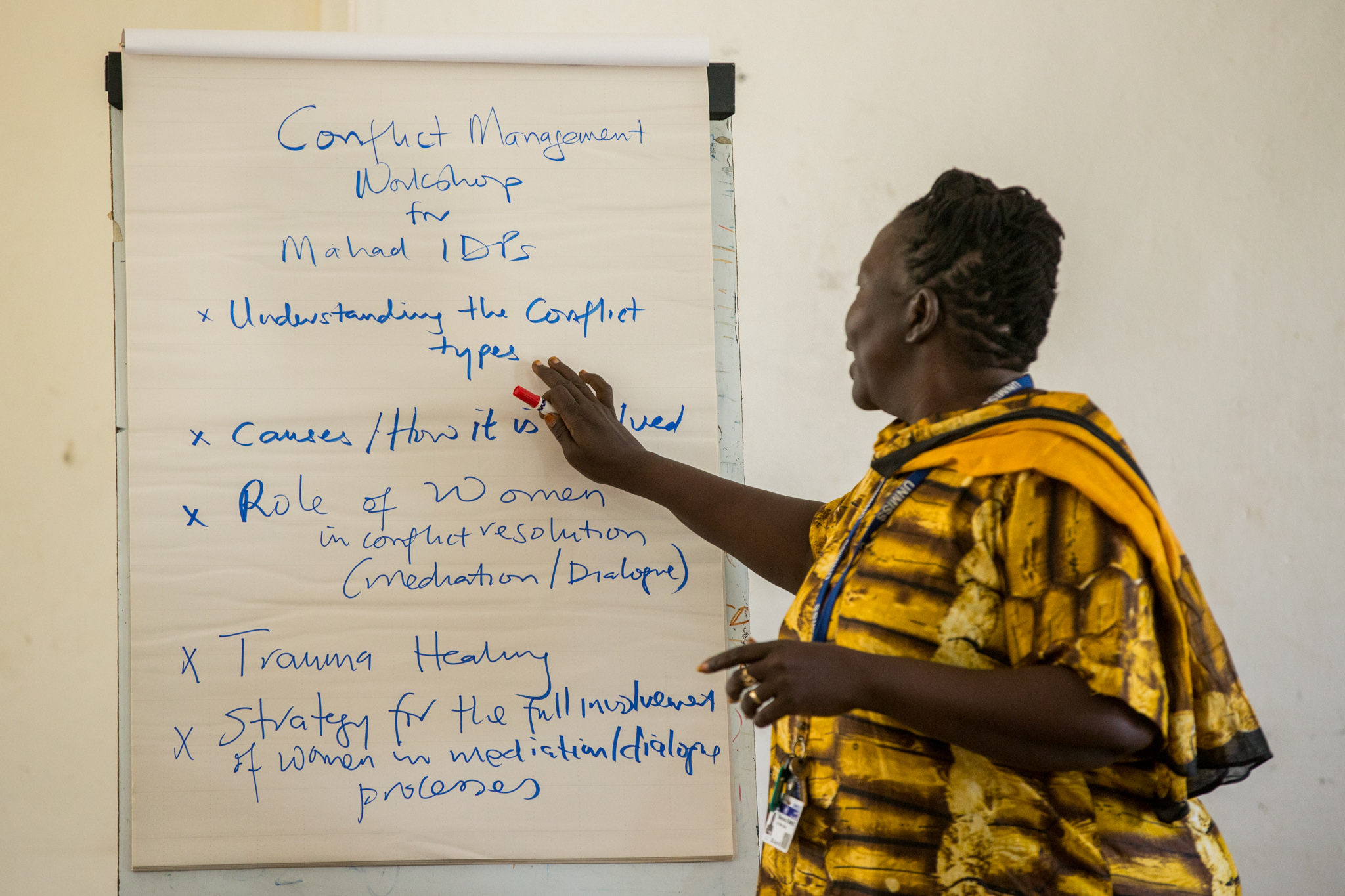

Photo credit: UNMISS via flickr

The field of Peace Education emerged after World War I and II when educators began to teach topics of peace with the hope of avoiding future war. Since then, peace education has branched off into various areas of focus with their own methods of teaching. However, peace educators tend to hold certain philosophies which are often incorporated in their work:

- Violence in all of its forms (direct, structural, cultural) and unbalanced power relationships (social, political, historical, economic) limit the capacity for human development.

- Peace educators can provide students with information and experiences that lead to the knowledge, skills and worldviews that promote peace.

- By grounding the learning process in real-world problems, critical peace educators provide the best way of enabling student agency, democratic participation and social action.

- Classrooms can be areas of optimism and transformation. Critical peace educators can provide the analysis of how their classrooms are situated into larger social contexts and the importance of both the socially and economically privileged and marginalized to learn methods and strategies for peace.

In addition to transforming structures of violence, peace education also seeks to create new ways of advancing peace, social justice and human rights. In this article, the author provides examples of peace education programs or “pedagogies of resistance” that challenge systems of inequality and offer students a platform to broaden their understanding of social, political and economic systems and encourages the envisioning of equitable solutions to complex problems.

The author highlights indigenous Zapatista education programs in Mexico, early childhood education in Dalit communities in India, and Freedom Schools during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. These three examples of critical peace education were chosen because they all focused on challenging dominant cultural, economic and/or political narratives that contributed to marginalization. Although they differed by participation, these programs where structured around educating on systems of inequality, pride in one’s own background or heritage and the importance of participating for social change.

As an example, the Zapatista revolutionary movement formed autonomous communities in the Chiapas region of Mexico challenging the Mexican government’s social, political and economic marginalization of its indigenous population. This mistreatment carried over into the schools many of Mexico’s indigenous youth attend. To address this issue, the Zapatista movement created an autonomous education system that protected indigenous culture, values and rights. The movement provided education geared towards the empowerment of rural communities and the awareness and analysis of injustices caused by centuries of abuse and inequality.

In the Dalit communities of India, one peace education program worked to provide a sense of moral strength bound by common ideology and social values that were previously lacking in a community once known as ‘untouchables’ at the margins of Indian society. Freedom schools during the United States civil rights movement used peace education to spark creativity and empowered young adults to identify problems in their community and create proactive ways to address the problems through social action.

The author envisions two opportunities to bridge initiatives and movements that adopt “pedagogies of resistance” with peace education theory. First, students can study and evaluate various peace education programs, thus leading to the improvement and proliferation of these programs. Second, by utilizing the lessons learned from the study of “pedagogies of resistance”, students can create context-specific practices that incorporate analysis, education and action.

Contemporary Relevance:

In almost every society there are marginalized groups that have suffered from inequality and mistreatment from their government or the more privileged and elite members of society. Organized resistance – long-term and short-term – takes place at many levels. Understanding the contributions that pedagogies of resistance can make toward changing the context in the educational realm carries great potential. As evident by the continued success in Mexico, the United States and India, peace education as a whole, and pedagogies of resistance in particular, can support these communities and address areas of inequality or injustice.

Talking Points:

- Peace education programs are a successful way to educate on and overcome social inequality.

- Peace education programs can be adapted to address different social, political and economic systems of injustice and inequality.

- Peace education programs adjusted to their context can connect analysis, education, and action for social change.

Practical Implications:

‘Pedagogies of resistance’ provide important opportunities to learn from successful methods of peace education and the potential to adapt this style of education to other areas of injustice or inequality. By continuing to analyze and report on best-practices, practitioners can further develop educational methods to address local issues as well as help integrate peace education into mainstream education by making success stories known to the broader public. All this can be done in a deliberate attempt of merging what is useful in general approaches and models with an eye toward adapting those within a given social context.

Keywords: resistance, peace education, social justice

Continued Reading

- Voice of Witness-Non-profit promoting human rights and dignity of the voices of people impacted by injustice through curriculum, oral history book series and education program (www.voiceofwitness.org)

- Educate in Resistance: The Autonomous Zapatista Schools by Angélica Rico (https://roarmag.org/essays/zapatista-autonomous-education-chiapas/)

- Contesting Zapata: Differing Meanings of the Mexican National Idea by Patrick Hiller (http://www.japss.org/upload/8hillercontestingzapata.pdf)

Citation

Monisha Bajaj (2015) ‘Pedagogies of resistance’ and critical peace education praxis, Journal of Peace Education, 12:2, 154-166, DOI: 10.1080/17400201.2014.991914