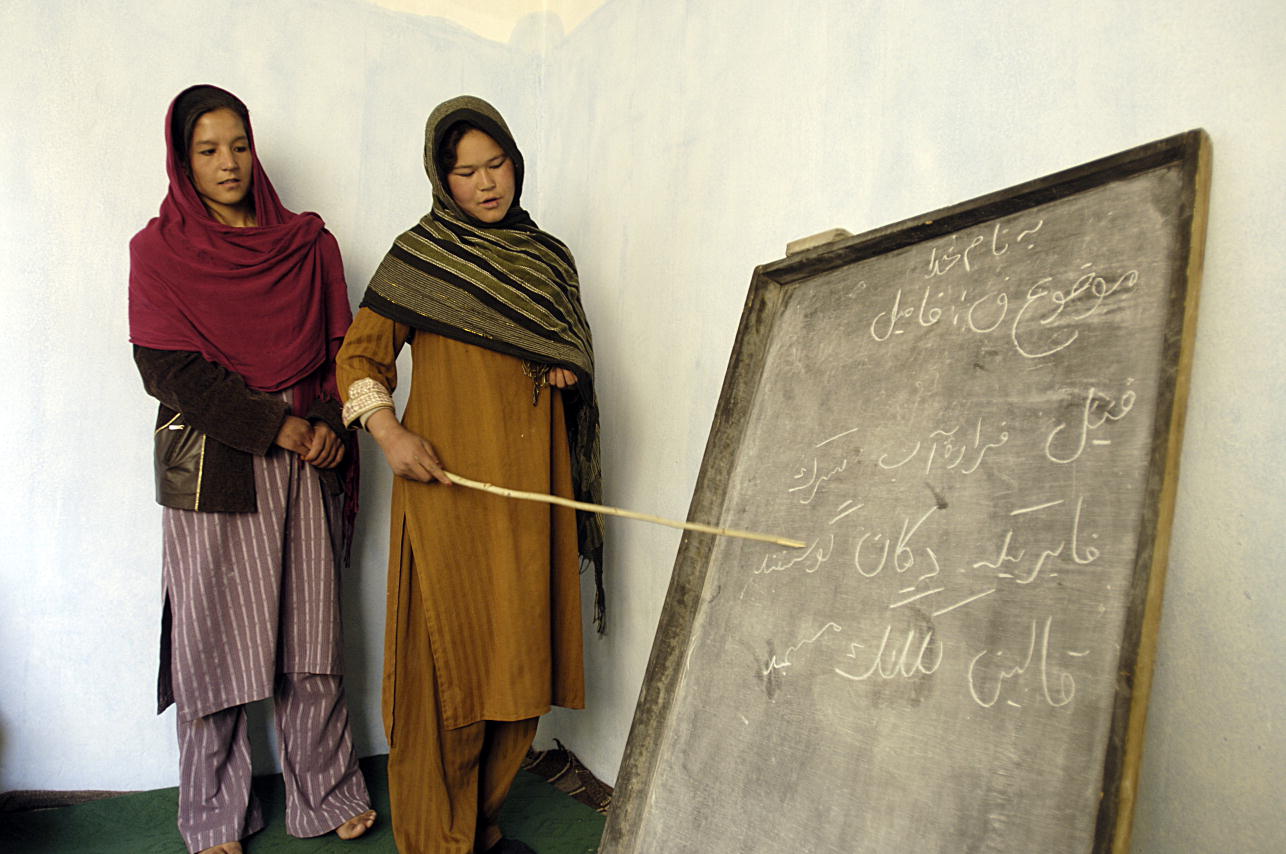

Photo credit: DFID – United Nations Photo via flickr

This analysis summarizes and reflects on the following research: Fabra-Mata, J., & Jalal, M. (2018). Female religious actors as peace agents in Afghanistan. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 13(2), 76-90.

Talking Points

In the context of female religious actors engaged in peacebuilding in Afghanistan:

- Women comprised less than a quarter of the Afghan religious peacebuilders network examined, and most of them were engaged in peacebuilding work focused on education, including teaching peace and conflict resolution from an Islamic perspective or raising awareness in their spheres of influence about what Islamic sacred texts say about peace.

- Although female religious actors face more hurdles than their male counterparts, their knowledge of Islam can be a powerful way to “overcome social barriers” and legitimize their role as peacebuilders, enabling them to both “reach beyond” traditional spaces and make the most of those already available to them.

- Knowledge of Islam opens up opportunities for women to work with male religious actors in ways that are beneficial for peacebuilding, especially when they can take on the mediation of a family- or community-level conflict together, leveraging their distinct forms of access with different people.

- Religious knowledge protects female peacebuilders in some measure against allegations of foreign/western influence, providing them with greater local legitimacy and respect with which to do their peacebuilding work.

Summary

Although recent scholarship has focused on both women and peacebuilding and religious peacebuilding, there has been scant attention paid to the role of female religious actors in peacebuilding. The authors of this research aim to “give voice” to female religious actors working for peace in Afghanistan, both to recognize their work and to gain a fuller understanding of religious peacebuilding in the country. They are curious to find out “how local female religious actors understand and work for peace.”

By “religious actor,” the authors mean someone who is “assigned…to function as in charge of a Mosque, to serve as a member of the Shuras (councils) at the district or provincial levels, and/or to lead educational teaching activities.” Women in Afghanistan are not granted leadership roles in mosques, but they can serve in the other two capacities (and are also granted some respect as religious figures if they are married to mullahs). The authors interviewed twenty female religious actors in 2017, from diverse provinces, ethnic groups, and sectarian affiliations (15 Sunni, 5 Shia), but all part of a network of religious peacebuilding actors in Afghanistan. Of the 464 members of the network, only 108 were women—many of them teachers at schools, madrassas, or universities.

The authors also carried out a statistical analysis of the types of activities conducted by members of the religious peacebuilders network, which could be broadly grouped into three categories: “conflict resolution” (at the family or community level), “peace pedagogy and awareness raising,” and “facilitation of dialogues between non-state armed groups, communities and state officials.” Female members were found to engage predominantly in educational activities, which constituted well over half of their overall activities, compared to one-fifth of men’s overall activities. These educational activities might include teaching peace and conflict resolution from an Islamic perspective, or raising awareness within their families—or more publicly through Facebook—about what Islamic sacred texts say about peace.

The qualitative findings are grouped under five main themes. The first two relate to how the women define peace (mostly as the absence of direct violence but also as individual or group welfare) and what motivates them to work for peace (predominantly a moral obligation grounded in religious belief, shaped by the harms caused by war).

The third theme relates to reflections on the role of religious actors in peacebuilding. Most startling was that the women interviewed assumed the term “religious actor” referred not to them but rather to men—those religious actors who lead congregations and therefore have a particular kind of access to and authority in the community, making them influential peacebuilders. When asked specifically about female religious peacebuilding actors in Afghanistan, the women underscored the importance of this role but mainly within limited spheres of influence: their families and other women. But, crucially, their religious knowledge served to amplify their influence within—and beyond—these traditional spheres. As the authors put it, “[w]hereas gender determines to a large extent the spaces for women’s peace engagement, religious literacy not only increases the opportunities for women to work for peace but also enlarges those very same spaces.” For instance, such women may teach peace beyond the family in schools and madrassas or “gain acceptance to mediate in intra-family conflicts as well as inter-family, community-level conflicts related to customary practices,” contexts where they, unlike male mediators, would have access to the women involved. In a country where religion is so powerful, “religious literacy [is] an empowering force” that garners respect for women peacebuilders who have it—respect they might not otherwise enjoy. One respondent noted how Afghan women engaged in peacebuilding can often be branded as “western” (and thereby delegitimized), but if they demonstrate religious knowledge people will pay attention.

Fourth, knowledge of Islam also creates opportunities for female religious actors to coordinate with male religious actors in ways that contribute to peacebuilding in the country: either by referring disputes to them that may not be seen as appropriate for women to mediate or by jointly taking on conflicts to mediate, with each accessing the community members to whom they have distinct access.

Finally, female religious actors face numerous challenges in their peacebuilding work, including disdain, disregard, verbal aggression, humiliation, or discouragement. Many women, however, reported overcoming “initial skepticism within [their] communities” and ultimately earning the support of most of the community for their work.

Although female religious actors face more hurdles than their male counterparts do, their “religious knowledge is a powerful means to overcome social barriers and facilitate peacebuilding work,” enabling them to both “reach beyond” traditional spaces and make the most of those already available to them; it also opens up opportunities to work with male religious actors in ways that are beneficial for peacebuilding.

Informing Practice

Two findings here merit further discussion. The first is that religious literacy can provide a powerful form of legitimation for women peacebuilders, who may not otherwise be taken seriously in a particular context, whether Afghanistan or elsewhere. This finding speaks to a broader insight that peacebuilders are more effective when they can speak to and connect with traditional values and sources of meaning in the community, especially when building peace requires challenging social norms. The ability to connect in this way may be especially important for those actors who do not automatically enjoy sufficient prestige or authority, which is often the case with women. Therefore, to the extent that women peacebuilding organizations in Afghanistan (and other countries where religion is a powerful force) can include religious actors in their ranks, cultivate religious literacy in their membership, and draw on religious perspectives in their efforts, they should do so—as long as doing so does not fundamentally violate their core principles. Such an approach should not be seen as a form of cynical calculation but rather as respectful recognition of the fact that there are many paths to understanding and transformation—and that religious belief can be an important one for many people.

The second key insight here is that women’s spheres of influence—though limited—can be extremely valuable when it comes to peacebuilding efforts, both in limiting the violence of armed conflict and terrorism and in limiting other forms of violence affecting women and girls. With the recent surge of interest in CVE (countering violent extremism), one area that has received much attention is the ability of mothers to influence their sons away from so-called “extremist” violence. But women’s influence in the family goes beyond CVE—especially with religious knowledge, they can enter into conversations with loved ones about the religious bases for both peace and violence of any type, providing a counterpoint to narratives these family members may be hearing from other sources. In addition, women peacebuilders’ access to other women outside the family can have ripple effects as these women in turn influence their family members. It also provides a means to address sources of insecurity that might otherwise go unnoticed if only male peacebuilders are available to mediate family and community conflicts in a particular area. With attention to either sphere of influence, we must of course be careful not to assume that all women take on traditional roles limited to these spaces or, at the other end of the spectrum, that women always possess sufficient power within these spaces to influence others in the ways desired (though, as noted, religious literacy contributes significantly to that power). In other words, while it is worthwhile to validate and support women’s peacebuilding efforts in these spaces, doing so should be coupled with recognition of women’s peacebuilding beyond them (in schools or other institutions in the public sphere, as noted here) and with broader struggles to challenge patriarchal systems and bring about gender equality.

Continued Reading

Grande, N. (2016, April/May). Religious actors for peace in Afghanistan. Retrieved March 2, 2020, from https://norad.no/globalassets/publikasjoner/publikasjoner-2016/ngo-gjennomganger/religious-actors-for-peace-rap-in-afghanistan.pdf

Marshall, K., & Hayward, S. (2011). Women in religious peacebuilding. Peaceworks Report No. 71. United States Institute of Peace, Washington, DC. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/publications/women-in-religious-peacebuilding

Kadayifci-Orellana, S. A., & Sharify-Funk, M. (2010). Muslim women peacemakers as agents of change. In Huda, Q., ed., Crescent and dove: Peace and conflict resolution in Islam. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Myers, E. (2018, April). Gender & countering violent extremism. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from http://www.allianceforpeacebuilding.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Gender-and-CVE-FINAL-1.pdf

Associated Press. (2020, February 21). US, Taliban truce takes effect, setting stage for peace deal. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2020/02/21/world/asia/ap-as-afghanistan-peace-talks.html?searchResultPosition=8

Keywords: religious peacebuilding, women, peacebuilding, gender, Afghanistan, mediation, peace education

The following analysis appears in the Special Issue on Peacebuilders in Volume 4 of the Peace Science Digest.