This analysis summarizes and reflects on the following research: Payne, C. R., & Swed, O. (2023). Disentangling the U.S. military’s climate change paradox: An institutional approach. Sociology Compass, 18(1), 1-16.https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.13127

Talking Points

- The U.S. military is a major contributor to climate change and other forms of environmental harm and a powerful political actor that acknowledges the threat of climate change.

- The U.S. military’s approach to climate change prioritizes increased resilience, adaptation plans, and mitigation; yet these actions have fallen short “of what is required to mitigate the military’s contributions to climate change” in a meaningful way.

- The U.S. military’s approach to climate change prioritizes “mission effectiveness” and believes that emissions cuts come at a trade-off .

- A strategic global retreat could mitigate the environmental harms by the U.S. military through base closure, ending unnecessary weapons production, and ending unnecessary deployments.

Key Insight for Informing Practice

- This research offers concrete policy recommendations to address the climate crisis by pressuring political leaders and policy makers to change what is meant by mission effectiveness—namely, to recognize emissions cuts as in support of national security. Coordinated efforts from all parts of society—including media or labor—can help make this change a reality.

Summary

The U.S. military is the world’s largest institutional emitter of greenhouse gases. Estimates suggest that the U.S. military (alone) emitted more than 1.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases between 2001 and 2017.[1] Yet, the U.S. military is among the most vocal institutions raising concerns about the national security implications of climate change. Corey R. Payne and Ori Sweed explore this complicated relationship wherein the military is both a major contributor to climate change and a powerful political actor that acknowledges the threat of climate change. The authors examine the military as an institution to identify practical ways to limit the military’s environmental harm, concluding that a “strategic retreat from its global-spanning presence” is the best way.

Scholars have described the military’s role in causing environmental harm as a “treadmill of destruction,” wherein militaries, as institutions, seek to expand in ways that fundamentally damage the environment. U.S. military activities can be described as a treadmill of destruction through the “massive consumption of fuels and raw materials,” the production of weapons and other supplies, and the pollution and waste resulting from its activities. The military’s large network of bases is a good example of these elements in action. The military owns massive amounts of land that is scarred by weapons testing and toxic waste. In addition, maintaining this network of bases, through the transport of personnel and supplies, currently requires the emission of incredibly high levels of greenhouse gases.

The military is fully aware of the risks of climate change. Since the early 2000s, the Pentagon has produced multiple reports that lay out different future scenarios and key national security vulnerabilities. Key areas of concern are the risks of extreme weather on military infrastructure, the risks associated with the “continued reliance on fossil fuels” and “mission dangers [such as] conflicts, migration, and upheavals stemming from ecological destruction [and] new battlespaces (such as the melting Arctic)[.]” Overall, the U.S. military has determined that social collapse is an inevitable outcome of the climate crisis and “views its job as not to fundamentally change this future, but to instead prepare for it—to ensure that the United States will be among the ‘winners’ of the unfolding climate catastrophe.”

The U.S. military approach to climate change prioritizes increased resilience, adaptation plans, and mitigation. Yet, despite these efforts, outside experts argue that “the military’s response has been far short of what is required to mitigate the military’s contributions to climate chance,” underscoring the fact that “the Pentagon does not fully grasp the extent to which it has contributed to ecological degradation.” Here the authors use an institutional lens to speculate about how the military might be trying to reconcile its position as both a polluter and a stakeholder They derive two intersecting institutional logics that explain the military’s approach: (1) a climate response logic “that recognizes the urgent threat that the climate crisis poses and that understands the role humans play in driving ecological degradation,” and (2) a military effectiveness logic that “is guided by the military’s perceived ability to counteract potential adversaries across a wide range of arenas and scenarios.”

These logics are understood as being in opposition, as “there is a fundamental tradeoff between military effectiveness and non-marginal emissions cuts.” As a result, the logic of military effectiveness is prioritized over cutting emissions. Further, emissions cutting may only happen if it is perceived as supporting mission effectiveness and not as a standalone goal. Since the idea of effectiveness is conditioned by other “social, political, and international forces”, there is an opportunity to (re)shape what is meant by effectiveness to include meaningfully limiting greenhouse gas emissions as a form of national security.

The authors conclude by describing how a strategic retreat could mitigate environmental harms by the military. They offer four “easy places for policy makers” to start a strategic retreat: (1) shutting down bases that have no military need, (2) closing unnecessary weapons productions lines, (3) ending unnecessary overseas deployments, and (4) closing foreign bases. While they acknowledge that the military, as a political actor, as well as weapons manufacturers, may be resistant to these changes, they nonetheless argue that “a reduction of the military’s footprint would not only help in the fight against climate change by reducing military emissions but would also free up fiscal capacity to be redirected toward broader green energy implementation and civilian infrastructure for responding to climate change.”

Informing Practice

Cutting military greenhouse gas emissions is a critical pathway to lower overall global emissions and the prevention of the worst outcomes of the climate crisis. The authors of this research offer several policy recommendations in support of a global strategic retreat of the U.S. military. They identify reachable goals, highlighting bases or supply chains that are unnecessary from a national security/mission effectiveness perspective and that are maintained for political reasons. To realize these goals, lots of different groups/sectors across society can exert pressure on political and military leaders to commit to such changes.

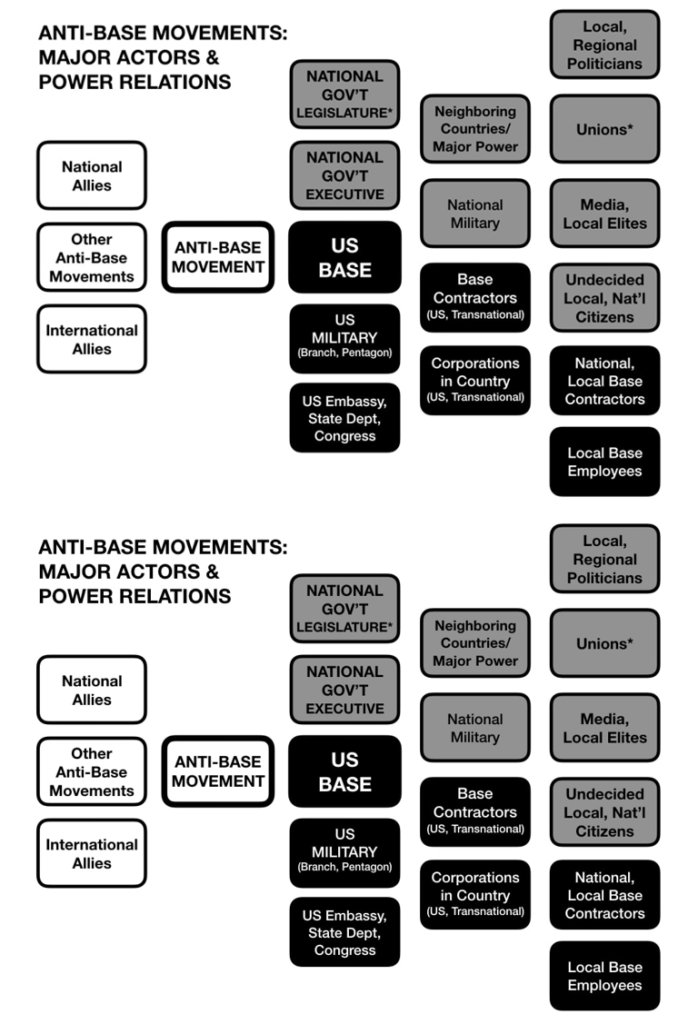

The image below is from research by David Vine on anti-base movements outside of the U.S.[2] White shapes correspond to anti-base movements and their allies, black shapes refer to base supporters, and grey shapes identify related stakeholders who can be moved into the pro- or anti-base camps. While this research focuses specifically on foreign anti-base movements outside of the U.S., this image helps to identify similarly situated stakeholders in the U.S. who can exert pressure in favor of a global strategic retreat.

For example, consider unions and, specifically, the work force of the military industrial complex. Research from the Costs of War project interviewed defense contractor employees in the U.S. and the U.K. to find out what their views were on climate change and their sector’s role in exacerbating the climate crisis. They found evidence of workers concerned about climate change and their sector’s role in contributing to it, showing real interest in a green transition and smaller military. This research creates a potential opening to build relationships among movements and sectors—say, among anti-militarist or climate organizers and defense sector union workers—to work towards a common goal of reducing emissions and creating good union jobs in the green energy sector.

The media is also a significant player. Media and the larger information environment are critically important to shaping worldviews and creating broader awareness of social and political problems. Very few popular media outlets in the U.S. critically examine defense policy, the military-industrial complex, or the relationship between the military and climate change. Independent or non-profit media outlets—like Inkstick, Common Dreams, Propublica, or Mother Jones— fill an important gap in the coverage of these issues. But more can be done to pressure larger media outlets and non-traditional media to link military spending and climate change, supporting a wider pressure campaign for reducing the size of the military.

As Payne and Sweed’s research suggest, key to this change is (re)shaping what is meant by mission effectiveness. Unabated greenhouse gas emissions from military activities can no longer be accepted as a necessary cost of a strong and effective military. Instead, they should be understood as a critical weakness, ultimately undermining the safety and security of both American citizens and those around the world, not only through climate change’s direct threats to human security like natural disasters, food insecurity, and natural resource depletion but also through its exacerbation of the very national security risks (e.g., mass migration) that the U.S. military is intending to “protect the nation” from.

Continued Reading and Watching

Gaffney, A. (2024, December 10). As teenagers, they protested Trump’s climate policy. Now what? The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2024, from https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/10/climate/youth-climate-movement-sunrise.html

Al Jazeera News. (2024, June 4). Militaries are fueling the climate crisis. All Hail the Planet. Retrieved December 16, 2024, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RFjAjO0dl3M

Bell, K. (2023). U.K. and U.S. defense workers’ views on the environmental costs of war and military conversions. Costs of War. Retrieved December 16, 2024, from https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/papers/2023/DefenseWorkers

Pemberton, M. (2023). From a militarized to a decarbonized economy: A case for conversion. Costs of War. Retrieved December 16, 2024, from https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/papers/2023/DecarbonizedEconomy

Vine, D. (2020). The United States of War: A global history of American’s endless conflicts, from Columbus to the Islamic State. University of California Press. Retrieved December 16, 2024, from https://www.ucpress.edu/books/the-united-states-of-war/hardcover

Crawford, N. (2019). Pentagon fuel use, climate change, and the costs of war. Costs of War. Retrieved December 16, 2024, from https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/papers/ClimateChangeandCostofWar

Vine, D. (2019). No bases? Assessing the impact of social movements challenging US foreign military bases. Current Anthropology, 60(19). Retrieved December 16, 2024, from https://www.basenation.us/uploads/5/7/1/7/57170837/vine_david_no_bases__current_anthropology_2019.pdf

Organizations

Costs of War: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/

Quincy Institute: https://quincyinst.org/

Rethink Media: https://rethinkmedia.org/

Inkstick: https://inkstickmedia.com/

Common Dreams: https://www.commondreams.org/

Fridays for Future: https://fridaysforfutureusa.org/

Zero Hour: https://thisiszerohour.org/

Keywords: demilitarizing security, U.S., military spending, climate change, environment

[1] To put that into context, the United States’ GHG emissions total over the same period, excluding military emissions, was approximately 120 billion metric tons. This data was sourced from the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory Data Explorer: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ghgdata/inventoryexplorer/#iallsectors/allsectors/allgas/gas/all

[2] Vine, D. (2019) No bases? Assessing the impact of social movements challenging US foreign military bases. Current Anthropology, 60(19). https://www.basenation.us/uploads/5/7/1/7/57170837/vine_david_no_bases__current_anthropology_2019.pdf

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons